|

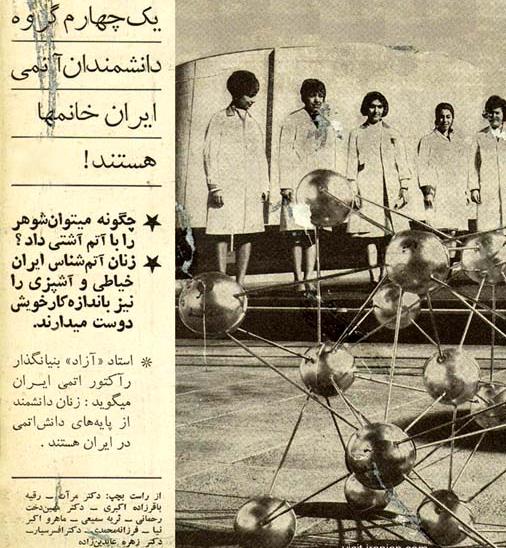

Suzanne Maloney is an expert on Iranian politics, energy and economic reform in the Middle East, and U.S. policy toward the region. Prior to her position as a senior fellow with the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings, she was a member of the State Department’s policy planning staff; a Middle East advisor at ExxonMobil Corporation; and director of a Council on Foreign Relations task force on America’s Iran policy. Author of Iran’s Long Reach and contributor to such works as Which Path to Persia? Options for a New American Strategy toward Iran, she is also founder and editor of Iran@Saban, an insightful blog about politics in and policy concerning Iran.

|

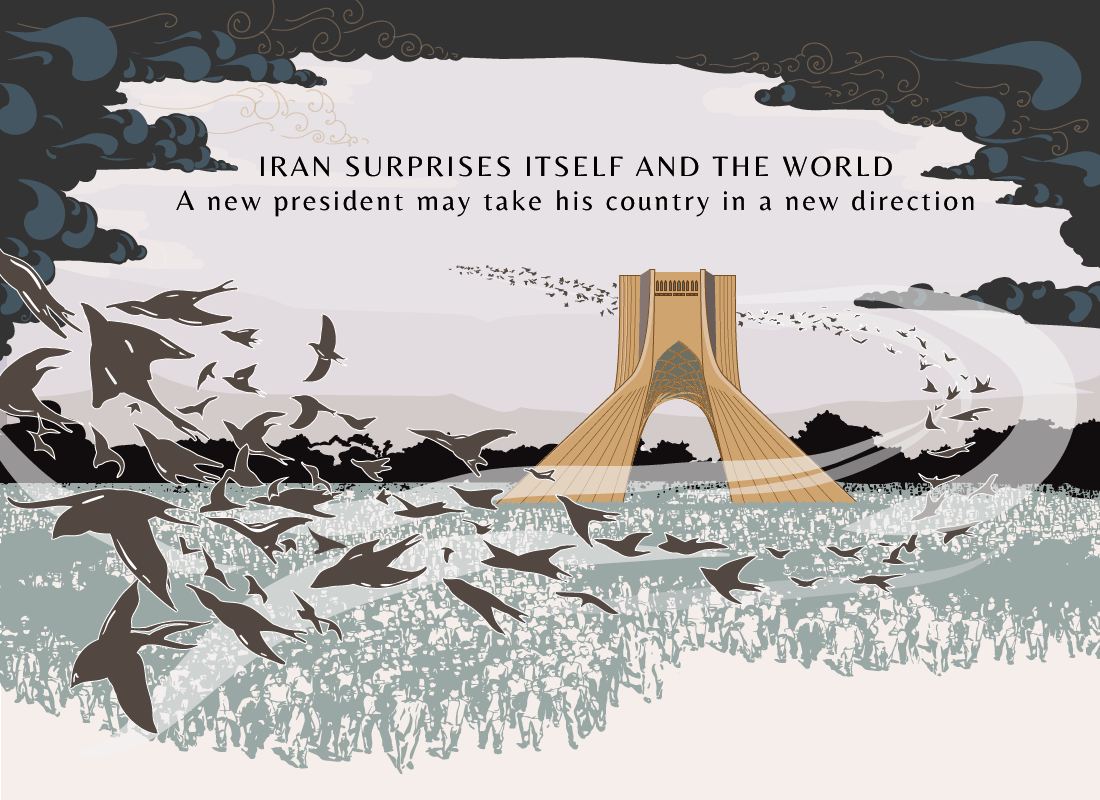

The sycamore trees that line the northern stretches of Vali Asr Avenue in Tehran arch overhead like a canopy. In the winter, their snowy branches frame a view of the Alborz Mountains where Tehranis escape to hike or ski. On a summer day, the leaves filter the sun and smog in the affluent northern neighborhoods, and you can watch the temperature rise by ten degrees as you inch your way southward in the city's infamous traffic toward the heart of old Tehran.

Tehran’s historic Vali Asr Avenue on a snowy day.

Getty Images

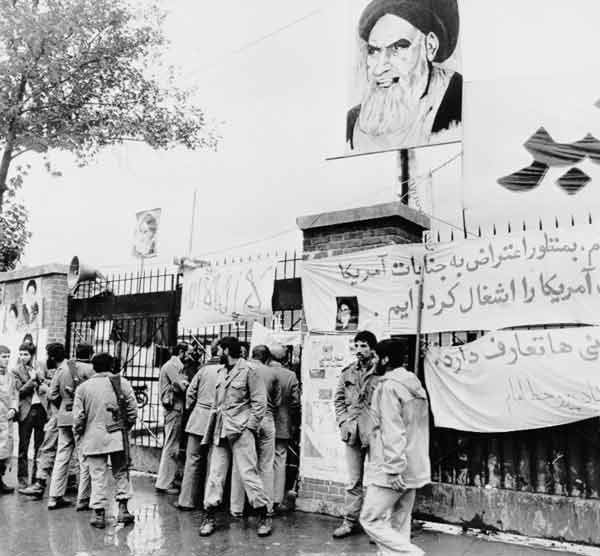

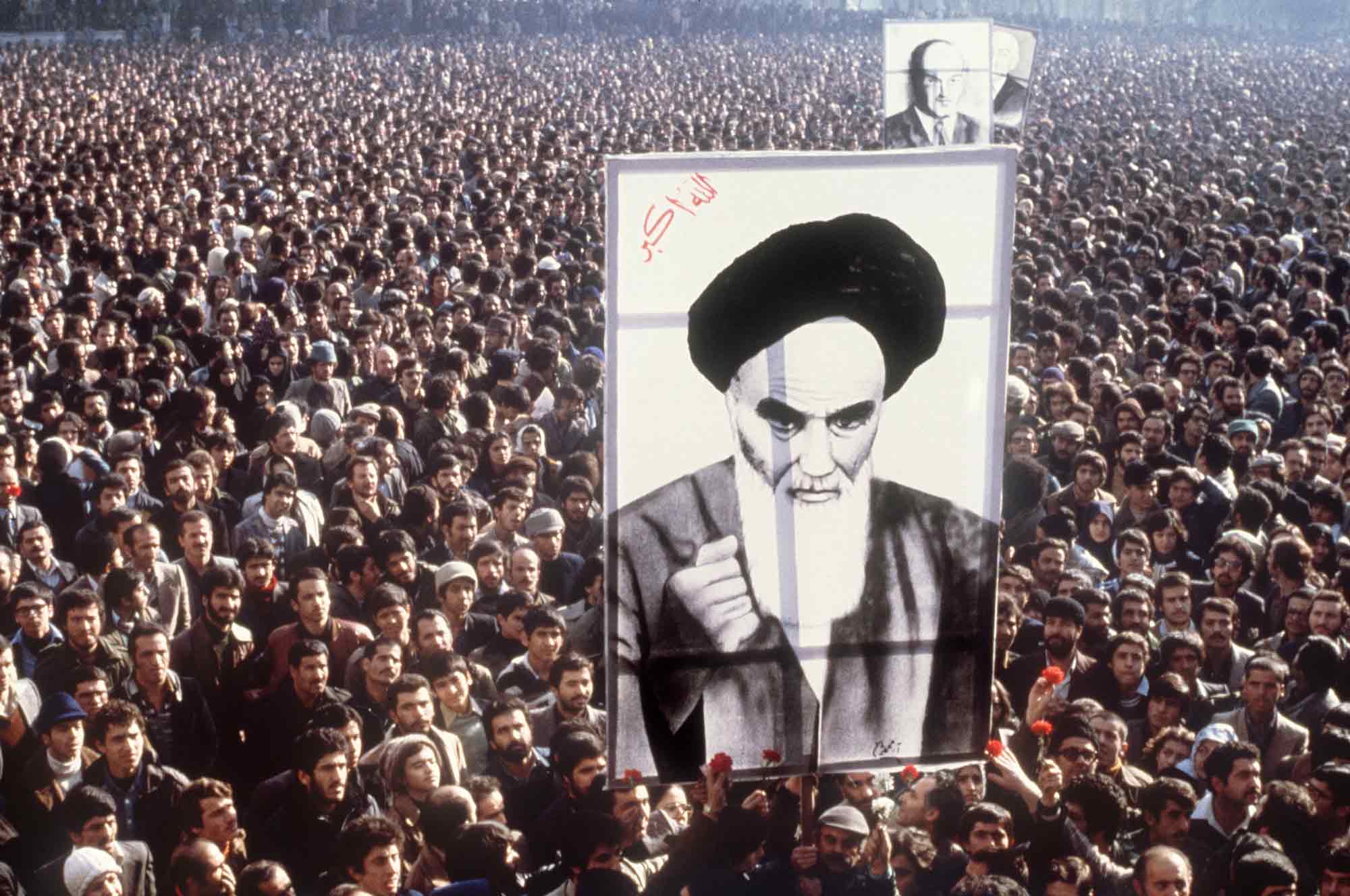

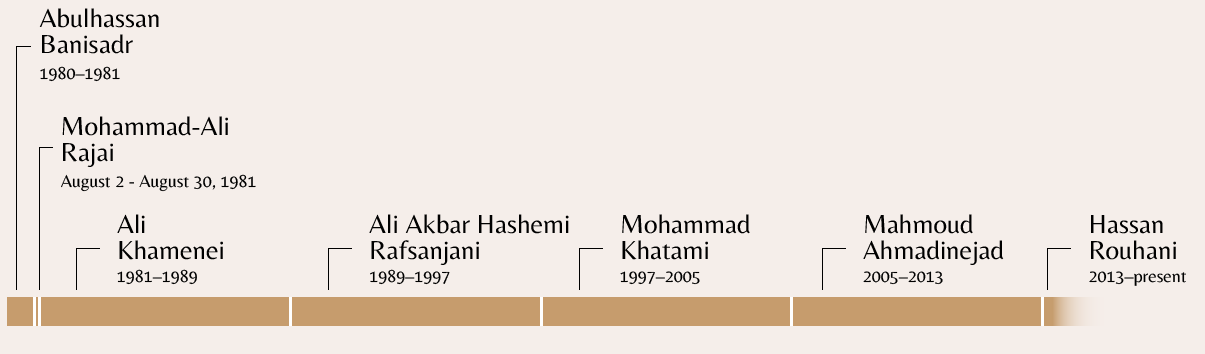

Vali Asr is said to be the longest street in the Middle East; and sometimes it feels like the only straight path in a nation whose course has been highly unpredictable and intensely complicated ever since the 1979 revolution which ousted the secular, pro-American shah and installed a theocracy led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. It was on Vali Asr, 18 years later, that young Iranians erupted in joy in the largest spontaneous public demonstrations the capital had seen since the revolution. The immediate cause for celebration in 1997 was the national team's World Cup qualification, but for many it was a belated response to the recent election of a president who promised reform. Mohammad Khatami's victory represented a moment when the country appeared on the cusp of change again. His promises went largely unfulfilled, however, doomed by the intractability of the defenders of Iran's religious orthodoxy—among them the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

For Shi'a Muslims, the phrase 'Vali Asr' symbolizes hope in a just future; for Iranians, the revolution has brought anything but.••

|

|

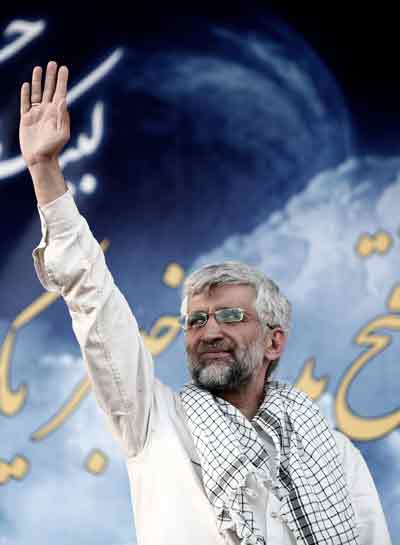

Hassan Rouhani

Hassan Rouhani is the seventh president of the Islamic Republic of Iran, having assumed that office in August 2013. Born Hassan Fereidoun in 1948 in northern Iran, he attended seminary in Qom and the University of Tehran, and later earned a doctorate from Glasgow Caledonian University in Scotland. Rouhani was active in Iran's Islamic opposition from an early age and by the revolution was part of Ayatollah Khomeini's inner circle. He served five terms in parliament and in other senior leadership positions throughout his career, and led Iran's nuclear negotiations until 2005. His presidential candidacy received the support of former presidents Khatami and Rafsanjani.

Yet, on the eve of another election in 2009, Iranians returned to Vali Asr in another powerful display of the will of the people. Tens of thousands of Iranians linked arms in a human chain that stretched the full 12 miles of Vali Asr to express their support of reformist candidate Mir-Hossein Mousavi. Less than a week later, however, huge crowds gathered there again, this time to denounce the apparently rigged victory of the incumbent, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a man infamous for his bigotry and provocative policies. The protestors' initial chants of "where is my vote?" met with police batons and bullets. The violence that ended the demonstrations, and the show trials and other Stalinist tactics that followed, suggested that the theocracy no longer saw the need for even the fig leaf of semi-orchestrated elections, and instead had devolved to a more naked authoritarianism. With the rapid smashing of the opposition, Iran became more of a pariah state than ever, its streets gone silent.

Tehran, June 9, 2009: Supporters of Iranian presidential candidate Mir-Hossein Mousavi, dressed in his signature color green, attend a campaign rally. Mousavi ran as a reformist and challenged the official tally, sparking massive protests. He has been held under house arrest since February 2011.

Getty Images

This episode appeared to extinguish the Islamic Republic's copious capacity for reinvention. But something happened along the way to the latest election, in June 2013: Iran's political narrative once again defied expectations. A brief and unprecedentedly outspoken campaign gave voice to criticisms of the regime that might once have landed some of the candidates in jail. In the end, it was the candidate who appealed most forcefully for a new path who won the presidency, with a resounding majority.

Like his mentor Rafsanjani a quarter-century ago, Rouhani appears to have been tapped to effect a turnaround—to staunch a crisis and salvage the revolution from its own failings.••

In the aftermath of the vote, throngs of Iranians once again poured onto Vali Asr for spur-of-the-moment street parties. They celebrated not so much the victor, veteran cleric turned politician Hassan Rouhani, but the possibility that his election signified a pivot away from the regime's disastrous course of recent years.

Hear how Iran first captured Suzanne Maloney's attention and why she remains optimistic about its future.Why she sees Iran as a country with an "incredible democratic history and a vibrant political dynamic…a land of opportunity and imagination."

|

|

Even if this proves true—even if Tehran is stepping back from the brink of its ruinous battle with much of the rest of the world—there is no guarantee that Rouhani's election will put an end to the uncertainty that has enveloped Iranian politics for more than three decades, or lessen the antagonism between the Iranian leadership and the West. Rouhani campaigned on a slogan of hope and prudence, two commodities that have been in short supply since the 1979 revolution. Delivering on that promise may prove the toughest course the Islamic Republic has yet had to navigate.