Matt Bennett is Senior Vice President for Public Affairs and a co-founder of Third Way. In that capacity, he has served as an adviser on gun policy to Sandy Hook Promise. He previously served in the White House as a Deputy Assistant to the President for Intergovernmental Affairs for President Clinton, where he served as the principal White House liaison to governors and covered a wide range of issues, including disaster response, Medicaid, immigration, education and others. Prior to that, Matt served in Vice President Al Gore's office. He was Communications Director of the Clark for President Campaign in 2004, and from 2001-2004 was Director of Public Affairs for Americans for Gun Safety.

It was the saddest roll call I’ve ever heard. “I’m Nelba; my daughter’s name is Ana; she was six.” “I’m Mark; my son’s name was Daniel; he was seven.” “I’m Nicole; my son’s name is Dylan; he’s six.”

And on it went, as we sat around the table of a sterile conference room at a DC law firm, the confused and confusing mix of tenses signaling the freshness of loss, the impossibility of comprehending it yet. It was late January 2013, barely a month after the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School, and these were the families of some of the victims. Eleven of them had somehow summoned the strength to come to Washington to meet privately with Vice President Biden, members of Congress and cabinet members. But they weren’t here simply to accept high-level condolences. They had come to listen and to learn about mental health and school safety policy. And they were preparing to wade into some of the roughest waters in American politics: the gun debate.

I was there to help them navigate those waters. The families’ DC-based advisor had invited my organization, Third Way—a group deeply involved with efforts to change the gun laws—to give them a sense of what they were in for.

They were preparing to wade into some of the roughest waters in American politics: the gun debate.

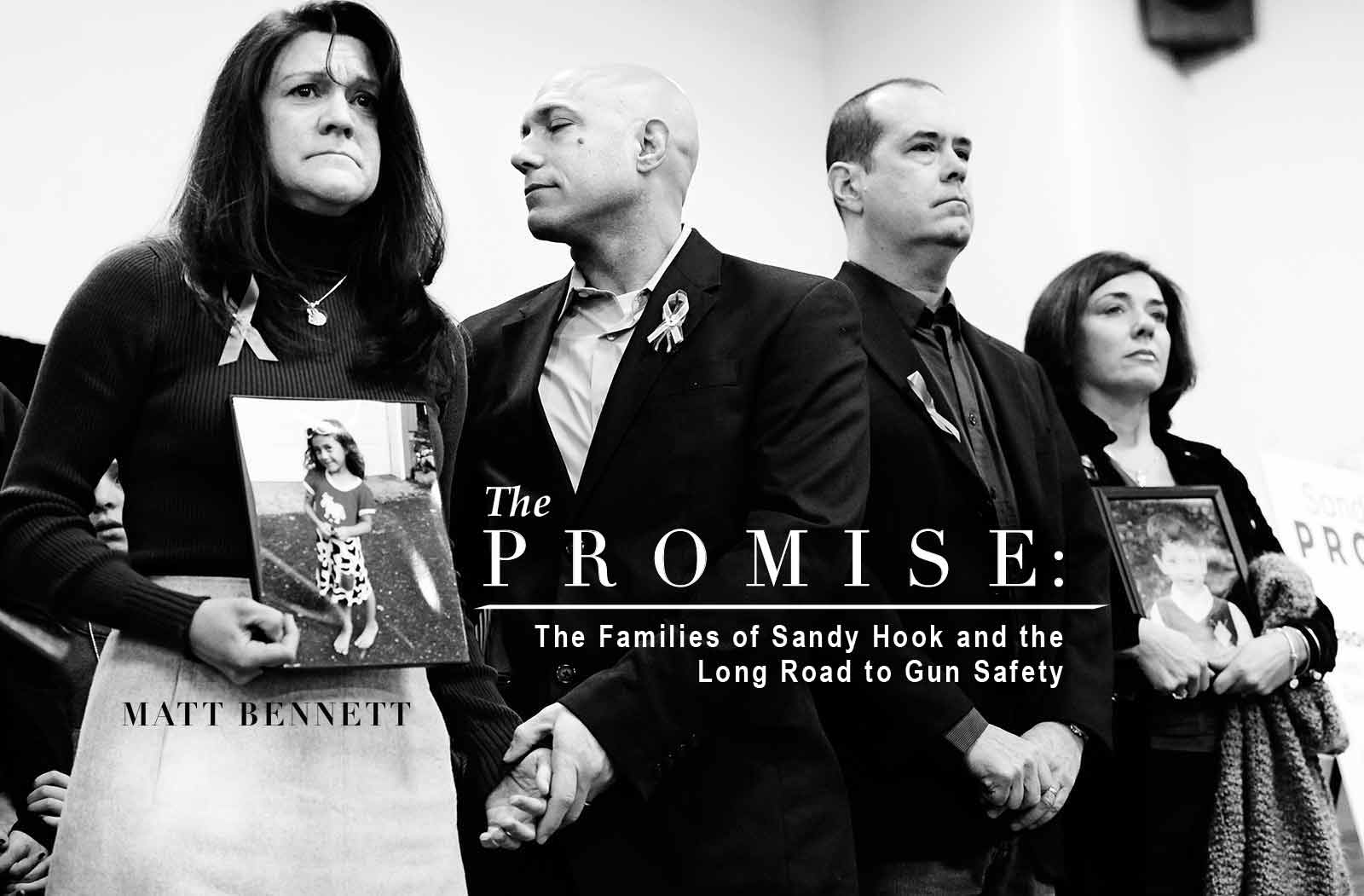

On January 14, 2013, Sandy Hook Elementary School family members held a news conference in Newtown, Connecticut to announce the launch of Sandy Hook Promise. It was exactly one month after the shooting that claimed the lives of 20 students and six adults, and wounded 14 others. L-R: Sandy Hook parents Nelba Márquez-Green, Nicole Hockley, Mark Barden, Jackie Barden

AFP/GETTY IMAGES/Don Emmert

At that moment, with teddy bears still adorning makeshift shrines all over Newtown, it seemed that progress on gun safety would be inevitable. President Obama had given a resolute speech in Connecticut vowing to fight for change, and members of Congress seemed to be reacting more like parents than politicians. Senator Joe Manchin, a gun-owning Democrat from West Virginia, said on television what many Americans were saying at their kitchen tables: “They are killing our babies; this has got to stop.”

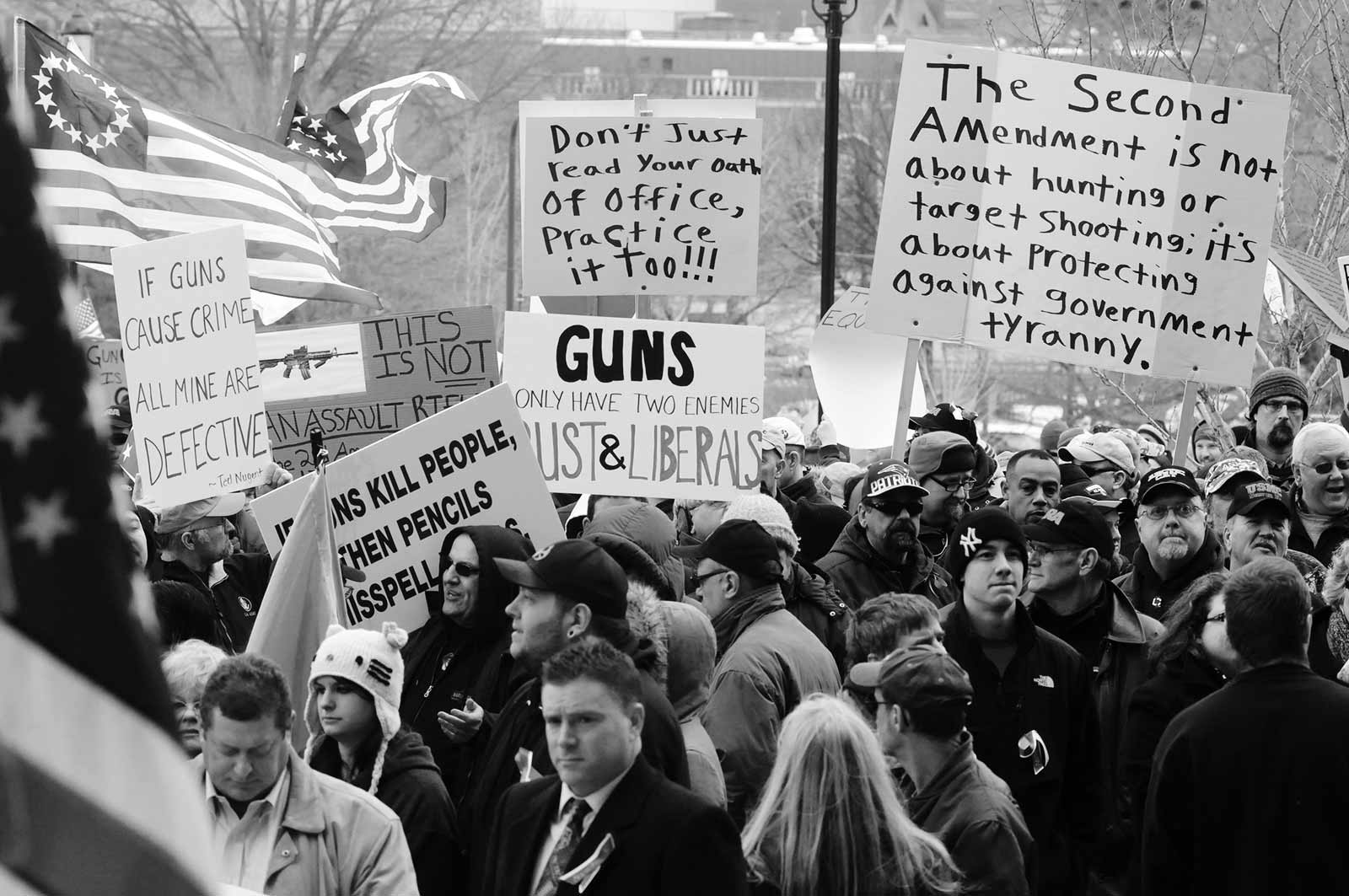

As Joe Manchin knew, however, it was never going to be that simple. Time and again, high-profile gun crimes—from assassinations to mass shootings—had seemed to galvanize public opinion. Yet time and again, this sense of urgency had faded, as the gun lobby slowed momentum in Congress to a crawl and then, often, to a halt.

I stood before the Sandy Hook families on that day in January to brief them on the basics of gun policy and politics. These are smart, educated people. They assumed that, in the wake of this horror, Congress would pass some long-overdue gun safety measures. By then, however, this much was already clear to the political classes: there wasn’t going to be a renewed ban on assault weapons or high-capacity ammunition magazines, no matter how wrenching the scene in Newtown. Congress just didn’t have the courage to take such a step. The Senate wouldn’t pass it, and the House wouldn’t even consider it.

When I broke this news to the families, one of the mothers let me know, gently but firmly, that I had screwed up. “Don’t tell us what can’t be done, because we just aren’t prepared to hear that,” she said. “Tell us that it could take time, which we can accept, because we’re in this for the long haul. And tell us what we can do now to honor the memory of our children.”