Jaffer has long contended that PRISM is,

in its essence, a violation of the Fourth Amendment as well as

the First Amendment right to freedom of association. He was the

lead attorney for a group of ACLU clients — lawyers, journalists,

and human rights advocates — in a challenge to Section 702 that

the Supreme Court rejected, in a familiar 5-to-4 split, in

February 2013. That was, of course, pre-Snowden. But the leaks

have shown no sign of nudging the judiciary toward anything

like a consensus. Quite the contrary. In December alone, a U.S.

district judge in the District of Columbia resoundingly

declared the phone records program unconstitutional, and 11

days later another federal judge, in Manhattan, just as

forcefully upheld the program.

That same month, President Obama — a

chief executive who is highly deliberative by nature and

trained in constitutional law — received a report from a panel of

five former government officials recommending new or tightened

restrictions on NSA practices.

A number of those proposals were

reflected in Obama's speech at the Justice Department on

January 17. He walked a fine line between responding to the

global outcry and, as he clearly saw it, protecting the NSA's

ability to protect America. Among the measures he announced was

an immediate order for the NSA to limit its surveillance of

phone records to connections that were two degrees of

separation (or "hops") from a known or suspected terrorist,

rather than the three degrees that had been permissible before.

The president also called on the executive branch and,

ultimately, Congress to come up with a plan for warehousing the

data in private hands, with a requirement that counterterrorist

agencies seek access the records on a case-by-case basis.

As Obama made clear, many features of

his plan require review and refinement within the executive

branch. As the designated custodian of these records, the

private sector, too, will have an important role to play, and

not necessarily one it welcomes. The phone companies have been

understandably skittish about helping the government — as many

will see it — pry into the lives of their customers.

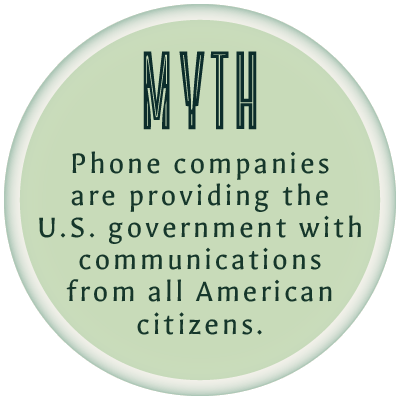

see fact

see fact

And then there is the legislative branch, which was the source of the restrictive laws on intelligence activities in the seventies and the eager partner of the executive branch in undermining those laws during the two pre-Snowden decades.

Many in Congress were quick to spin Obama's decisions and suggestions as consistent with their own. Wyden and two Senate allies, Udall and Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.), issued a joint statement in January saying they were "very pleased that the president announced his intent to end the bulk collection of Americans' phone records," even though the president had made no flat assertion to that effect.

Feinstein and her House counterpart,

Representative Mike Rogers (R-Mich.), said, more accurately,

that they were "pleased the president underscored the

importance of using telephone metadata to rapidly identify

possible terrorist plots," a task that they — like the

NSA — believe requires continuing bulk collection.

Jaffer shared their interpretation of

Obama's overall message — "He tinkered with the margins, but he

seems to have rejected, at least for now, any far-reaching

changes, which means that he has accepted, at least for now,

the proposition that the NSA should be collecting essentially

everything" — though not their reaction to it, because the bulk

collection is the very thing he and other critics want to see

changed.

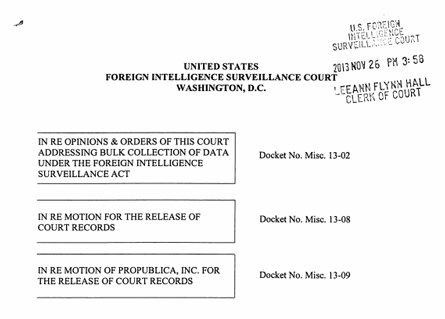

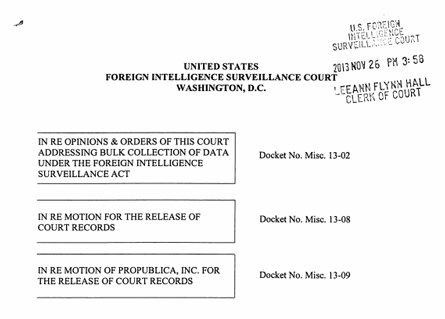

FISC court document on ACLU information requests (detail)

Source: FISC Courts

In March, the House Intelligence

Committee's ranking Republican and Democratic members said that

they were close to agreement on legislation that would end bulk

collection of phone records. Shortly thereafter, President

Obama unveiled a proposal that would do just that. Under the

new plan, the government would no longer systematically collect

and store Americans' calling data, which would instead reside

in the hands of phone companies. Only with permission from a

judge could the government obtain specific, suspect

records.

In at least one area of

reform— more transparency and accountability — there is a

degree of convergence among Wyden, Feinstein, Brenner, Jaffer,

and many others who differ over other aspects of surveillance

and reform.

Wyden has long since staked

out his objection to a "secret court" — "the most bizarre court

in America" he calls it — which deliberates behind closed doors

and hears only from government counsel, then issues

interpretations that are classified. "The law should always be

public," he says. "How do Americans make informed judgments

about policies if there's a big gap between the laws that are

written publicly and their secret interpretation?"

Wyden has long since staked

out his objection to a "secret court" — "the most bizarre court

in America" he calls it — which deliberates behind closed doors

and hears only from government counsel, then issues

interpretations that are classified. "The law should always be

public," he says. "How do Americans make informed judgments

about policies if there's a big gap between the laws that are

written publicly and their secret interpretation?"

Brenner agrees that "we have a massive

over-classification problem," adding, "Look, democracies

distrust power and secrecy, and intelligence organizations are

powerful and secret. The only way to square that circle is if

the public understands what the rules are and has reason to

think they are being followed." While he regards Snowden as "a

traitor and a scoundrel," he faults the government for not

having publicly revealed and explained the phone records

program years ago. Had that happened, the American people would

have had "the kind of debate that's happening now" — but in a

less sensationalized and more deliberative atmosphere.

It is ironic that in the wake of the

Snowden leaks the NSA took steps toward precisely that kind of

openness with its decision last December to allow Benjamin

Wittes and Robert Chesney, scholars in the Governance Studies

program at Brookings, to interview five top officials of the

agency at its Fort Meade headquarters. The result, posted

online as a series of Lawfare blogs and podcasts, was an

extraordinarily candid, sometimes eye-popping explanation of

the inner workings of the intelligence-gathering process, the

oversight and enforcement procedures, the relationship with the

private sector, the constant race to keep up with new

technologies, the means by which Snowden was able to pilfer the

material he publicized, and the steps that are being taken to

prevent another such breakdown in security.

But the NSA's decision to allow those

interviews, while voluntary, was almost surely due to the

public pressure it was under. Wyden and his congressional

allies have long urged that the government be required to make

periodic reports on its activities, to the extent permitted by

"protection of sources and methods" and other strong national

security needs. Wyden would also like to see disclosures of the

breadth of information collection and open acknowledgment of

violations of law by the NSA or other agencies. He believes

that such transparency would have a braking effect on excessive

surveillance.

Feinstein and her allies would also

require greater transparency, but not as much as Wyden

advocates, and mostly in the form of codifying in statute the

steps already taken by the NSA. Again, Brenner is thinking

along similar lines. He has written that the dilemma created by

the need to protect both privacy and national security "can be

resolved only through oversight mechanisms that are publicly

understood and trusted — but are not themselves entirely

transparent."

As President Obama recognized in his

January 17 speech, an additional way to ensure more fully

informed decisions by the FISA Court and to raise public

trust in its work would be to encourage or require that it hear

from independent voices rather than from the government alone.

In the speech, Obama called on Congress to establish a panel of

public advocates who would represent privacy interests before

the FISA Court, an idea that he had first floated the previous

summer. As Jaffer says, "When a court is presented with only

one side's arguments, it's inevitable that the court is going

to end up siding with that side more often than it ought

to."

Feinstein and Brenner as well as Jaffer

and Wyden favor some version of such a change, as do Alexander,

Obama, and most other players in the NSA drama; but Wyden and

Jaffer would give the advocates more power than most of the

others would. Feinstein, for example, would leave it to the

judges to decide in which cases to appoint "friends of the

court to provide independent perspectives," while Wyden and

Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.)

prefer a permanent office of "special advocate." The advocate

would have the right to oppose the government in important

cases; to ask to be heard even if uninvited by the court; and

to appeal surveillance court decisions with which the advocate

disagrees. Somewhere in this mixture of proposals there is

surely a compromise that will ensure that independent,

security-cleared lawyers will have the opportunity to expose

the weaknesses in the government's arguments without turning

every case into a legal donnybrook.

Feinstein believes that there is a

meta-problem more vexing and more important than the fate of

any one intelligence program. The biggest challenge, as she

sees it, is using the debate and reform of NSA activities to

begin repairing "the destruction of faith in our government," a

blow to national security and national morale that the Snowden

leaks have exacerbated.

She is surely right about that, and that

makes it all the more important to put the onus on the American

people's representatives in Congress to join the president in

making the tough choices. As Brenner says, "If you have to make

a recorded vote on whether to give this authority to an agency,

or if you're in an agency and have to decide whether you want

the authority, you're asking yourself how you're going to look

when the bomb goes off. And that's a scary position to be in.

That's called having responsibility. And people who've actually

got the responsibility talk and behave differently than people

who don't."

No one has more responsibility than

President Obama himself. While he is not commonly viewed as the

nation's Spymaster-in-Chief, that function does come with his

job. He sees the most highly classified intelligence every

morning. He is in a position to judge its utility over time

and, therefore, to make judgments about "the sources and

methods" by which it is collected. And the buck stops on his

desk if the system fails to anticipate a Pearl Harbor or a

9/11. No doubt that aspect of his job helps explain what seems

to some of his critics a disconnect between his strong civil

libertarian roots and his professorial knowledge of the

Constitution on the one hand, and his essentially protective

posture with regard to NSA surveillance on the other.

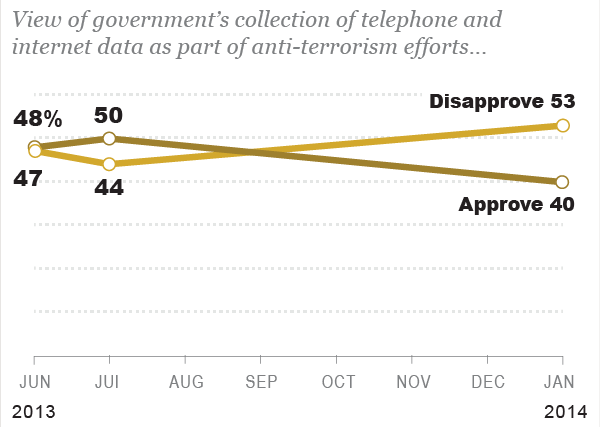

Whether the American people and their

representatives in Congress will support the president,

Feinstein, and others who want to maintain much of the status

quo depends on there being more public trust in government than

there is now. The distrust evident in the polls is directed at

both the legislative and executive branches.

In addition, there must be a critical

mass of the public willing to live with not just one permanent

conundrum but two. The first, which is at the heart of the

problem, is the inherent tension between national security and

individual privacy. The second, which is evident in the search

for a solution, is the severe limit on the degree to which

transparency can be reconciled with functions of government

that must be opaque — that is, secret — in order to be

effective.

The challenge is captured in the most

famous sentence that F. Scott Fitzgerald ever wrote, in an

essay three-quarters of a century ago: "The test of a

first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed

ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to

function." That is also the test of a first-rate intelligence

agency in the service of a robust democracy.

Join the conversation on Twitter using

#BrookingsEssay

or share this on Facebook.

This essay is available as an e-book at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and eBooks.

We invite you to explore all of the Brookings essays at thebrookingsessay.org

Like other products of

the Institution, The Brookings Essay is intended to contribute

to discussion and stimulate debate on important issues. The

views are solely those of the author.

Graphic Design and Illustration: Marcia Underwood

Web Development: Marcia Underwood and Kevin Hawkins

Videos: Director – George Burroughs;

Director of Photography – Ian McAllister;

Camera Operators – Sareen Hairabedian, Brianne Aiken;

Sound Mixer – Zachary Kulzer

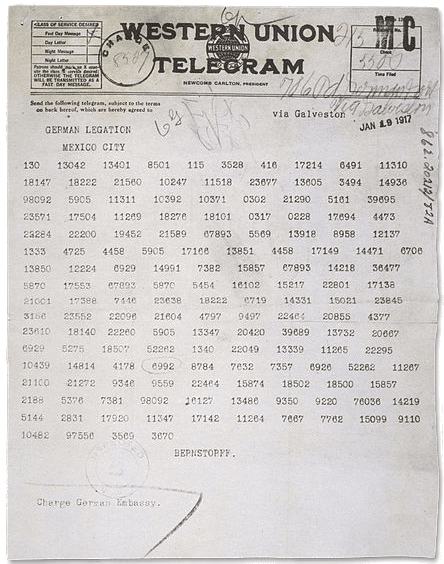

However, once the war had ended, President Herbert Hoover's secretary of state, Henry Stimson, famously shut down the "Black Chamber," a precursor of the NSA, which had begun intercepting and decoding foreign diplomats' cables in peacetime, too. "Gentlemen," Stimson harrumphed, "don't read each other's mail."

However, once the war had ended, President Herbert Hoover's secretary of state, Henry Stimson, famously shut down the "Black Chamber," a precursor of the NSA, which had begun intercepting and decoding foreign diplomats' cables in peacetime, too. "Gentlemen," Stimson harrumphed, "don't read each other's mail."

Wyden agrees with Jaffer. Phone records, he says, can be tremendously illustrative of a person's private life: "If you know who a person called and when they called and generally where they called from, you know a tremendous amount about them" — political and religious affiliations, sexual behavior and extramarital affairs, problems with alcohol, drugs, or gambling, medical conditions, and more.

Wyden agrees with Jaffer. Phone records, he says, can be tremendously illustrative of a person's private life: "If you know who a person called and when they called and generally where they called from, you know a tremendous amount about them" — political and religious affiliations, sexual behavior and extramarital affairs, problems with alcohol, drugs, or gambling, medical conditions, and more.

Wyden has long since staked

out his objection to a "secret court" — "the most bizarre court

in America" he calls it — which deliberates behind closed doors

and hears only from government counsel, then issues

interpretations that are classified. "The law should always be

public," he says. "How do Americans make informed judgments

about policies if there's a big gap between the laws that are

written publicly and their secret interpretation?"

Wyden has long since staked

out his objection to a "secret court" — "the most bizarre court

in America" he calls it — which deliberates behind closed doors

and hears only from government counsel, then issues

interpretations that are classified. "The law should always be

public," he says. "How do Americans make informed judgments

about policies if there's a big gap between the laws that are

written publicly and their secret interpretation?"