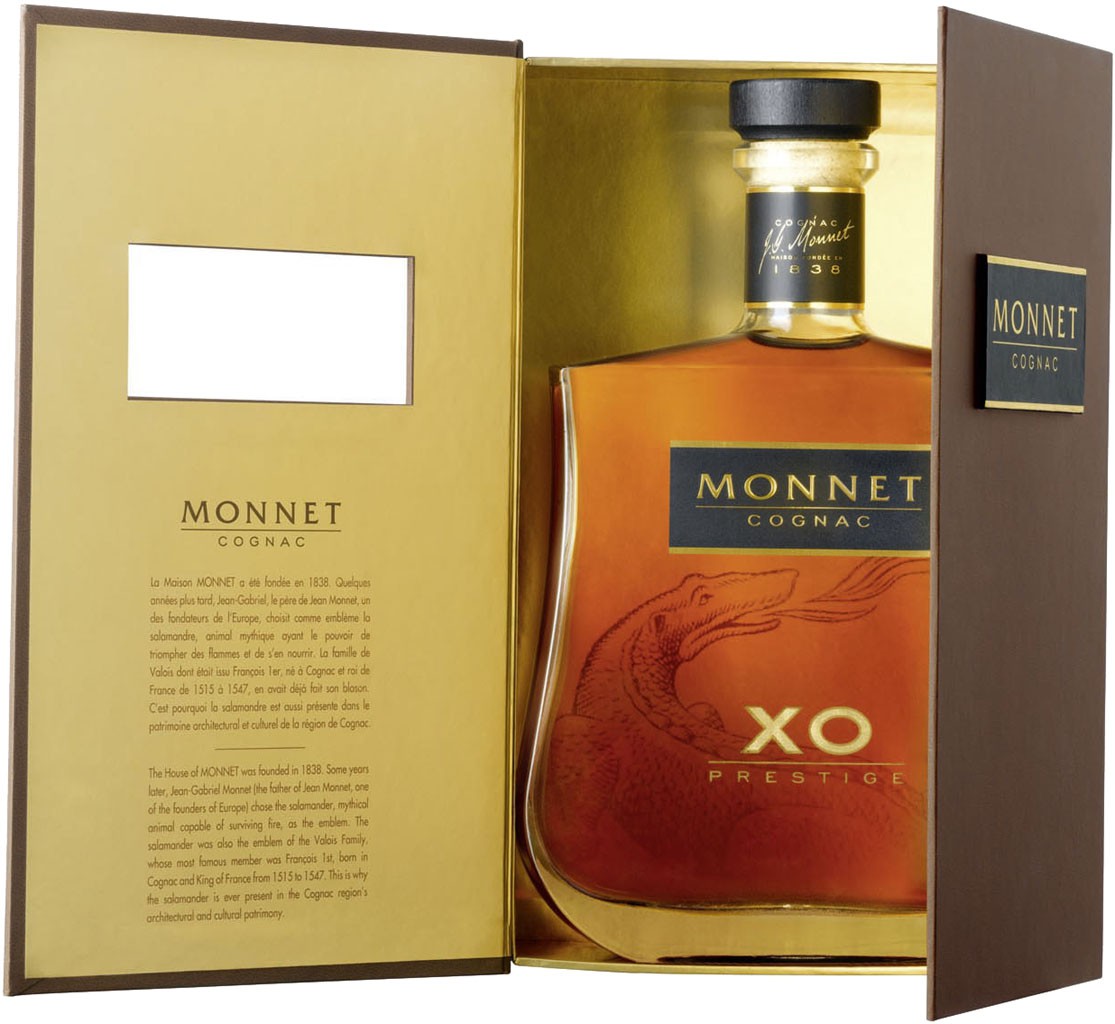

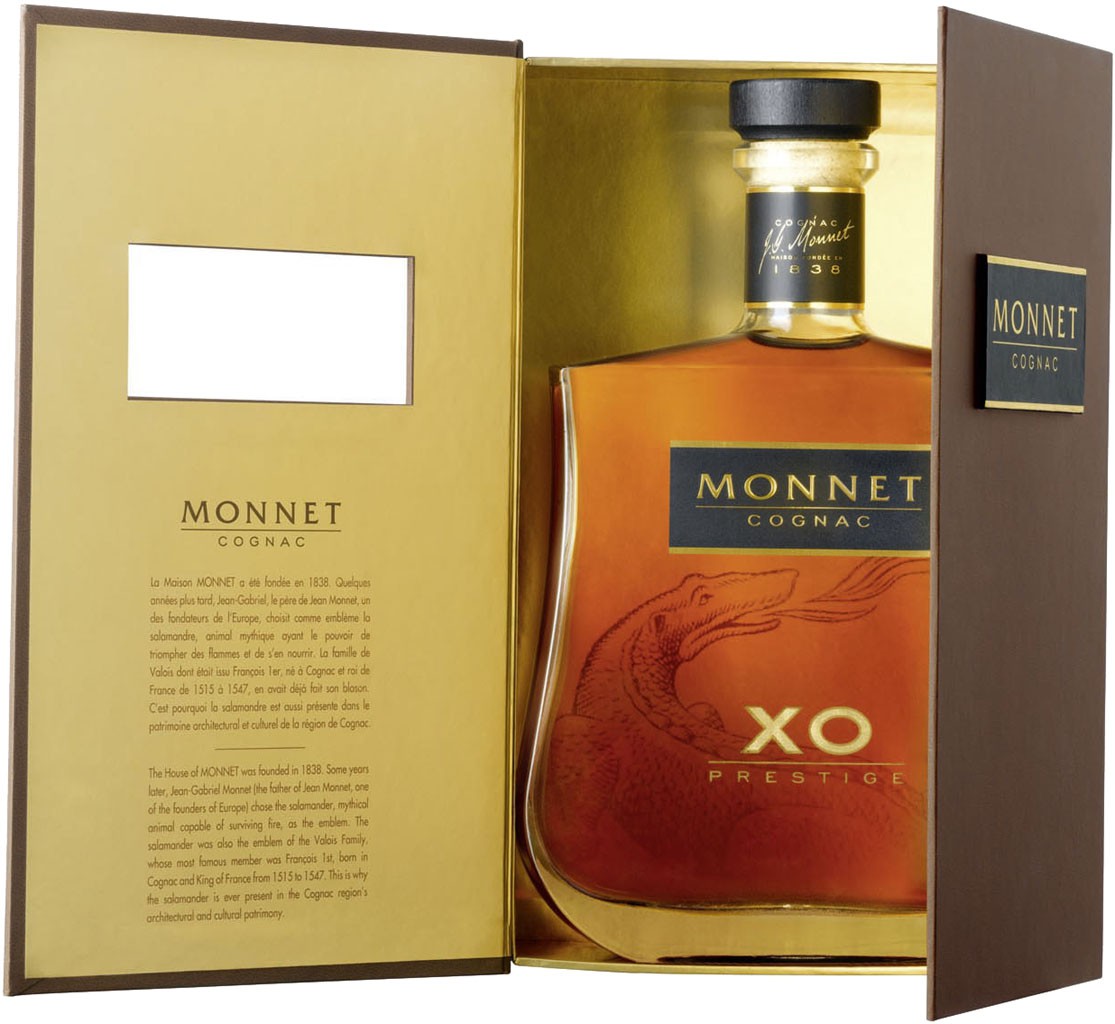

Monnet quit school when he was 16 to enter a profession that, directly or indirectly, sustained nearly everyone in the commune of Cognac: the manufacture and marketing of the spirits that bear its name. In his late teens and early twenties, he absorbed the basics of accounting and administration while working for the House of Monnet, which had been in the family since 1838.

At the end of his long life, Monnet described his birthplace as a “brandy town [where] one did one thing, slowly and with concentration.” That could have served as a motto for the singular purpose of his own life: the cultivation and marketing of a grand plan that would bring lasting peace to Europe.

Long after Monnet left the brandy trade, it continued to be a rich source of the metaphors he used to explain his lifelong undertaking. On brisk morning walks with friends in the countryside around his farmhouse in Houjarray, a village outside of Paris, Monnet would sometimes depart from discussion of the great issues of the day to reflect on what it took to make a fine cognac: harmony between the blessings of nature (climate, soil, and vines) and the virtues of human agency (patience in husbandry; care in fermentation, distillation, blending, and aging; thrift in good times, resilience in bad). He especially valued consistency of method and order: hanging the vines on meticulously laid-out trellises, fermenting the juices of the grapes for weeks, distilling them twice, then storing the result in neatly arrayed oak casks in dark cellars for anywhere from two years to a decade.

Once the contents were bottled, the final stage of the process—selling cases around the world—required this young man of country stock to become a globe-trotting cosmopolitan. He learned English as a child because it was “the language of our clientele,” and traveled widely around Europe as well as North America and the Middle East to promote the Monnet brand with its salamander emblem and, for the longest-aged, top-of-the-line product, the X.O. (“Extra Old”) rating.

Once the contents were bottled, the final stage of the process—selling cases around the world—required this young man of country stock to become a globe-trotting cosmopolitan. He learned English as a child because it was “the language of our clientele,” and traveled widely around Europe as well as North America and the Middle East to promote the Monnet brand with its salamander emblem and, for the longest-aged, top-of-the-line product, the X.O. (“Extra Old”) rating.

“equality is absolutely essential in relations between nations, as it is between people. ”

The firm was competing against the superpowers Hennessy and Martell. But brandy merchants also depended on cooperation with each other in order to broaden the global market for the benefit of all. An environment conducive to vigorous trade was a common good. That was an ethos that suited Monnet’s temperament. His inclination to listen carefully, combined with his ability to respond convincingly, argue tactfully, and probe for compromise made him a good businessman; it also turned out to be good training for diplomacy.

French troops waiting to depart for the Belgian front in August 1914.

Three Lions/Getty Images

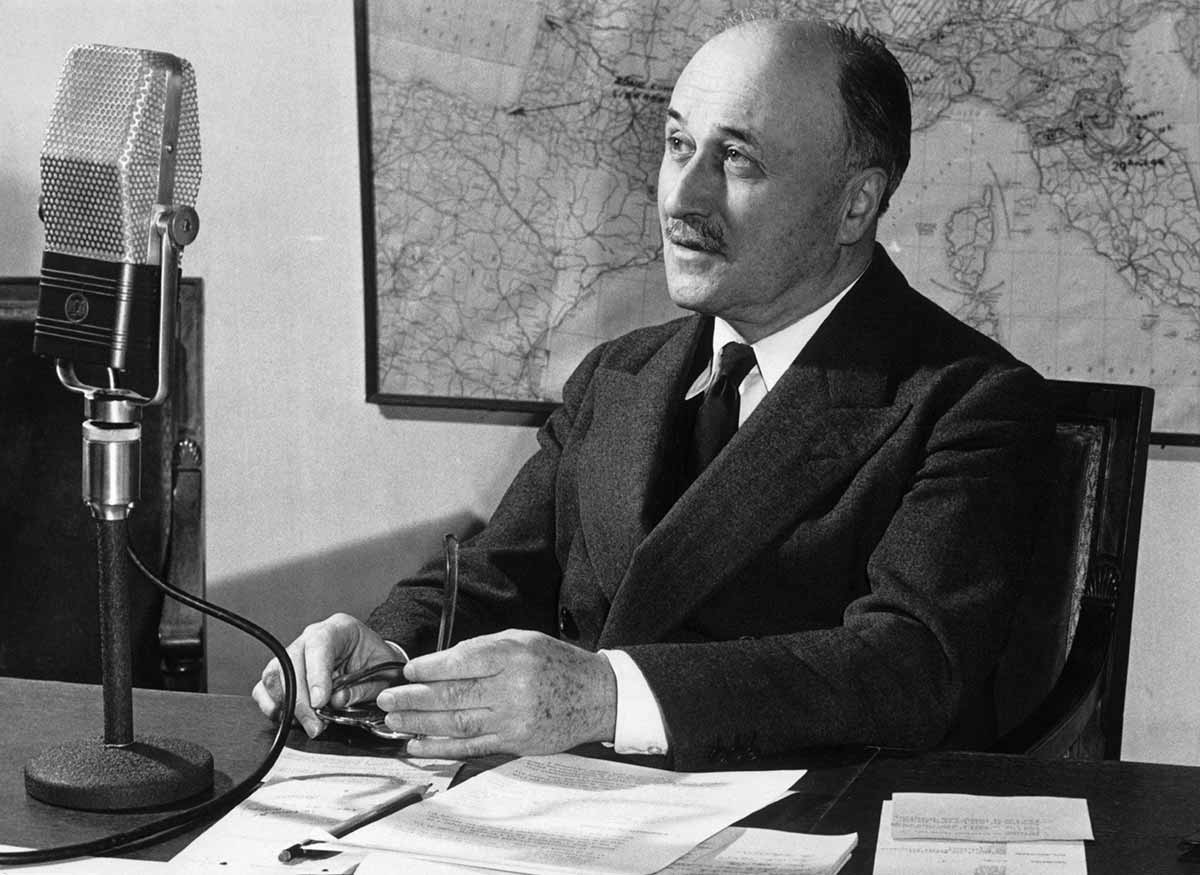

Monnet’s transition to what would become his life’s work occurred in the summer of 1914, shortly before the guns of August shattered the grand illusion that global interdependence would keep the major powers from ever again going to war. On his way home from London he learned, during a stop at the Poitiers railway station, that Germany had declared war on Russia and begun moving troops into Luxembourg, and France was mobilizing.

With the help of a family friend, Monnet went straight to the top of the French government to volunteer his services. Premier René Viviani was so impressed that he authorized the 25-year-old to negotiate the terms of an agreement between France and Britain to coordinate their production of armaments. Within three years, Monnet was helping Étienne Clémentel, the French minister of commerce and industry, to develop a proposal for a post-war “new economic order” based on Franco-British cooperation but open to other European countries as well.

The allies rejected that proposal at Versailles, but by then Monnet had patrons at the highest levels in Paris and London. When the League of Nations was established in 1919, they arranged for him to become its deputy secretary-general. Unfortunately, the unanimity principle under which the League was supposed to make decisions and take action kept it from doing much of either, and it was doomed almost from the start. Disillusioned, Monnet quit his post in 1923 to help his father cope with the family business, which was struggling.

After several years, Monnet became a peripatetic banker assisting governments with the modernization of their finances and infrastructure. He helped several Central European countries stabilize their currencies and advised Chiang Kai-shek on how to upgrade the Chinese railway system. Operating in a private capacity, Monnet had found a way to promote the integration of national economies as a basis for international commerce and peace.

Members of the Francist Party, one of many fascist leagues in France in the 1930s, march past a church in Paris. (February 13, 1934)

Getty Images/Keystone-France

But in the 1930s, the world was heading in another direction. Throughout modern history, economic distress has stoked the politics of fear, anger, and irrationality. Those, in turn, have often led to extremist, paranoid, repressive, protectionist, and sometimes aggressive government policies. This was never more true than during the Great Depression, which heightened the economic misery of war-torn nations, undermined democratic governments, and incubated fascism.

The Greatest Frenchman

Shimon Peres

Shimon Peres

Reuters/Chris Wattie

Peres on Monnet

Jean Monnet’s circle of friends, intellectual interlocutors, and admirers was global in scope and distinguished in its members. Despite the passage of more than half a century, President Shimon Peres of Israel remembers vividly conversations he had with the father of European integration.

In an interview with Strobe Talbott, Peres recalled asking Monnet in the late fifties about “his dream.” Monnet's answer: “We have to unite Europe because the alternative is that our skirmishes, our wars, our insults that have characterized Europe in the past will continue for the next thousand years. It's not enough that the Second World War is over. Unless we build a new world, the danger of war will hang over our heads.” As Peres noted, “Monnet’s vision was political, but his means were economic. A political vision inevitably generates opposition, so a pragmatic visionary must dress it up in a way that stresses its economic advantage.”

President Peres remembered with chuckle how he may have committed “a faux pas” when asked by a French newspaper, “Who do you see as the greatest Frenchman?” Without waiting for Peres’s reply, the reporter suggested that the right answer might be Napoleon. “I said, ‘No. I think Jean Monnet's greater than Napoleon. Why? Because Napoleon left after him a tomb while Monnet left a cradle in which a new, peaceful Europe was born.”

Monnet had long feared that the interwar period would be just that—a respite between global conflagrations. Like Keynes, he came to view the “war guilt” clause in the Versailles Treaty, which demanded reparations in the form of payments and transfers of property and equipment from Germany, to be a mistake. It was based, he believed, on “discrimination,” a violation of the core principle that “equality is absolutely essential in relations between nations, as it is between people.”

For Monnet, this was not just an ethical principle but a pragmatic one. Versailles had imposed a Carthaginian peace that would come back to haunt winners and losers alike by inciting, in little more than a decade, the worst kind of nationalism and racism. In 1935, at a dinner party on Long Island, Monnet heard from John Foster Dulles, then a Wall Street lawyer, the news that Hitler had just issued the anti-Semitic Nuremburg laws. “A man who is capable of that,” Monnet said to the table, “will start a war.”

By 1938, Monnet had returned to active public life, traveling around the Continent and across the English Channel as an adviser and envoy. His task, as he put it, was to convince

"civil servants to cooperate and exchange information between different ministries and different countries, so much so that the teams needed for joint action were already formed when the time came for decision. This is the dynamic of the balance-sheet, a page of figures which looks very much like those great account-books that my father taught me to read in Cognac when I was 16."

For him, the life lesson was that statecraft depends on sound economics as well as skillful politics—and the blending of the two into a single process in order to achieve the long-sought goal of the harmonization of international relations.

Monnet also shuttled back and forth across the Atlantic during those years. He already knew North America well, going back to a trip he made to Canada as a brandy salesman when he was 18 and numerous subsequent visits to the United States. He had quickly become an Americophile and would remain one all his life.

In Monnet’s view, American federalism proved itself during the 1930s as the best system of governance for countering the depredations of the Great Depression. The New World offered the Old World a model for its own future in another respect as well: the United States was the opposite of a Westphalian nation-state (France for the French, Germany for the Germans). On one of his many visits to New York, a Turkish taxi driver, seeing that his passenger was burly, swarthy and mustachioed, assumed he too was a Turk. Monnet found the incident more than amusing: it captured what he saw as one of America’s distinctive advantages. Here was a country-in-progress with an open door, constantly refreshing its citizenry with an influx of immigrants, drawing strength from their kaleidoscopic diversity. Even its food reflected the variety he so appreciated. While Monnet had a sophisticated palate, he enjoyed the occasional hamburger when traveling in the United States, not least because this iconic staple of American cuisine had a German name.

“There will be no peace in Europe if the states are reconstituted on the basis of national sovereignty… The European states must constitute themselves into a federation.”

The government that he dealt with in Washington pulsed with pragmatism, energy, and activism at a time when those back home had been sleepwalking into catastrophe for a decade. Monnet’s principal task in 1940 and the early months of 1941 was to urge President Roosevelt to come to the aid of Britain, and to pave the way for America’s entry into the war. Keynes believed that Monnet’s arguments were particularly effective with FDR.

Even in the dark hours when the Axis dominated most of the Continent, Monnet was thinking ahead about how to break the cycle of total war followed by a false peace. In 1943, he declared at a meeting of the French government-in-exile in Algiers, “There will be no peace in Europe if the states are reconstituted on the basis of national sovereignty…. The countries of Europe are too small to guarantee their peoples the necessary prosperity and social development. The European states must constitute themselves into a federation.”

There are few instances in history when a single statement of prescription and prophecy would so soon come to pass, and fewer still when the prophet himself would be a major agent in making that happen.

Two years later, after Germany and its allies surrendered, Monnet had his chance to begin the process of realizing his vision, though he got off to a rather uncertain start. As commissioner-general of the French National Planning Board, Monnet advised de Gaulle, the president of the provisional government, on how to reconstruct the French economy. One obvious means was to tap into Germany’s industrial potential, much of which was still intact. The sweeping recommendations he proposed are collectively known as the Monnet Plan. Its most conspicuous feature—the expropriation of coal from German mines in the Ruhr and Saar areas to fire the furnaces of French steel factories—was euphemistically called l’Engrenage (The Transmission). In addition to hastening the recovery of France, it inhibited Germany’s ability to rearm, a measure that was intended to be both punitive and preemptive.

“

The European Union was born out of a political concept: to get war out of the continent and to resolve everything peacefully.

”

-Javier Solana

Therein lies the irony: the Monnet Plan had an unmistakable aspect of Versailles déjà vu. It violated its namesake’s own principle of equality in inter-state relations. If it had remained in place for long, it would have crippled Germany’s own recovery and, very likely—just as Versailles had done—sown dragons’ teeth in the soil of Europe rather than the seeds of permanent peace.

Monnet, who generally eschewed the first person singular, rarely, if ever, referred to the plan by his own name. In his final years, he acknowledged that what the world knew as “the Monnet Plan” was an instance of French foreign policy “returning to the habits of the past.” The closest he came to justifying it was his observation that merging French and German resources vital to war-making “would reduce their malign prestige and turn them instead into a guarantee of peace.” At best, the plan that to this day bears his name was a temporary expedient—one that would be replaced by the proudest and most important accomplishment of his life.

Over the next four years, Monnet worked on a long-term successor arrangement that would be negotiated with Germany, not imposed on it. The agreement lowered duties and restrictions on coal and steel trade between France and Germany, bringing two vital sectors together under the aegis of a joint state-sponsored authority.

This bilateral accord was an exemplar of Monnet’s strategy for overcoming the national sovereignties that stood in the way of his vision. Applying the lessons of his youth in Cognac, he was laying the foundations, “slowly and with concentration,” for the “one thing” he knew he must do to bring about a federated Europe: create new economic facts on the ground. With the passage of time, national political leaders would see the virtue in thinking, deciding, acting, and, ultimately, governing on the pan-European level.

Monnet felt he had history on his side. The leaders of what had long been nation-states, along with the vast majority of their citizens, were used to buying and selling across borders. Commercial cooperation and its regulation had been an established norm of European life, since at least as far back as the 12th century, when the Hanseatic League had knitted together the economies of commercial centers, primarily along the North Sea and Baltic coasts. Immanuel Kant, a professor in the Hanseatic port of Königsberg (now Kaliningrad), had called the League a “confraternity of trade” and predicted that it might someday evolve into a united, democratic, and federative Europe.

Konrad Adenauer, the chancellor of post-Nazi West Germany, embraced Monnet’s vision of a 20th-century Hanseatic League that would end French control over the Ruhr and Saar coalmines, release Germany from economic purgatory and restore its prosperity. The result—a virtual merger of France’s and Germany’s coal and steel production—was to their mutual benefit, both economically and geopolitically. The agreement, it was said, would make another Franco-German war “not merely unthinkable but materially impossible.”

On March 19, 1951, Walter Hallstein (seated at left in glasses) and Jean Monnet (seated at right) signed the Schuman Plan, which became the European Coal and Steel Community under the Treaty of Paris a month later. Hallstein headed the German delegation and Monnet the French.

Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

That jubilant claim captured Monnet’s conviction that commercial cooperation could defuse the most fraught relationship on the Continent. The arrangement came to be known as the Schuman Plan, after France’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Robert Schuman, who negotiated it with Adenauer. Monnet seemed not to mind; he cared more about the consequences of his brainchild than credit for it.

Those consequences were dramatic and almost immediate. Monnet and Schuman moved quickly to open up the bilateral agreement to others. The 1951 Treaty of Paris brought in Italy, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. The result was the European Coal and Steel Community.

That last word was close to Monnet’s heart, not least because it ended in unity, his ultimate goal. The E.C.S.C. was the progenitor of the European Union and the fulfillment of the overarching plan Monnet had been developing and advocating for over 30 years. In a joint statement, Adenauer and Schuman proclaimed the magnitude and potential of their endeavor: “By the signature of this Treaty, the participating Parties give proof of their determination to create the first supranational institution and [to lay] the true foundation of an organized Europe.”

In his own writings, Monnet tended to steer clear of the word “supranational.” To him, it implied a superstate with power concentrated at the top rather than delegated, as much as possible, to subsidiary and largely self-governing units. But he wholeheartedly supported the rest of Adenauer and Schuman’s joint declaration.

In Monnet’s view, the key to solidifying the E.C.S.C. as a foundation for further expansion was the treaty’s establishment of an effective institution —the High Authority—to implement, oversee and administer its terms and goals. As Monnet often said, “Nothing is possible without men, but nothing lasts without institutions,” which he regarded as “the pillars of civilization.”

The High Authority of the E.C.S.C. was headquartered in Luxembourg. It was the community’s executive branch, empowered to make decisions on behalf of the six member states regarding the modernization and improvement of production, the development of a common export policy, and the improvement of working conditions in the coal and steel industries. Monnet was the natural choice for its presidency.

Jean Monnet presiding over a ceremony at the Belval factory in Luxembourg establishing the European Coal and Steel Community. (May 1, 1953)

Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

Other than his stint at the League of Nations 30 years earlier, this was the only post Monnet would ever hold at or near the top of an international institution. Significantly, in both cases, they were newly created international organizations. Also in both cases, his tenure was brief—only three years. As he often said, he loved inventing and starting organizations but not running them. Management bored him, and being an haut fonctionnaire made him uncomfortable: “No one has ever succeeded in making me do anything which I did not think desirable and useful, and in this sense I have never served a master. But I, in turn, have rarely obliged anyone to act against his will.”

Throughout his life, no matter what his position, his power was less ex officio and more that of persuasion. The cause he most wanted to advance was not administering European trade in coal and steel but laying the ground for an all-inclusive European federation. He resigned from the High Authority in 1955 to found an independent advocacy group referred to by everyone but him as the “Monnet Committee.” Its formal name was the Action Committee for the United States of Europe, which left no doubt as to its purpose and inspiration.

Monnet would spend the rest of his life pushing for the eventual incorporation of France into a robust European system of governance modeled on what was essentially an Anglo-Saxon invention developed by former British colonials. To that end he worked at mobilizing labor unions and political parties to support the carefully worded proposition that the nations of Europe “should delegate some of their powers to federal bodies.” The committee’s headquarters were in Paris, on Avenue Foch, about three miles from the Élysée Palace, which was the epicenter of a passionate, often obstinate dedication to national independence and exceptionalism so indelibly associated with Charles de Gaulle that it was called Gaullism.

Few political leaders in modern history have been more adamant about upholding the sovereignty of their nation—and in his case, protecting France against a resurgent Germany—than de Gaulle. He had been out of office when the Treaty of Paris was signed, and had opposed the creation of the E.C.S.C. In the late 1950s, he founded France’s Fifth Republic and assumed its presidency. While de Gaulle did support the creation of a common market in the late 1950s for what he called “the Europe of Nations,” he vituperated publicly against the very idea of an integrated and federative Europe, which he denounced as “the Europe of Jean Monnet,” warning that it would become a puppet of a “federator that is not even European”—i.e., the United States.

French Prime Minister Charles de Gaulle delivers a speech during his visit in Toulon. (July 14, 1958)

Raymond Darolle/Europress/Sygma/Corbis

De Gaulle and others sometimes mocked Monnet as “the great American.” Monnet did not much mind. To the bemusement of friends on both sides of the Atlantic, he fantasized, as he grew older, about taking an extended sabbatical to Arizona, in part because he thought that the climate would be good for his ailing lungs.

He never attained that goal, or two others that he wistfully confided to his friends: winning the Nobel Peace Prize and living to a hundred.

In 1975, when he was 86, and in declining health, Monnet decided that the Action Committee had served its purpose. The de Gaulle era was over, and the integration of what was then known as the European Community was gathering steam. He settled into his home in Houjarray and plunged into writing a 500-page reflection on his life and work, often with his wife of 40 years, Silvia, an Italian artist, painting at an easel nearby.

Monnet’s memoirs, which he finished three years before he died, radiated pride in the progress Europe had made and optimism about what the future held. But he registered disappointment over missed opportunities and failed projects, notably the stillbirth of a European Defense Community in the early fifties and, a decade later, the rejection of the United Kingdom’s application for membership in the European Economic Community (E.E.C.), as the common market was formally known. Both setbacks were largely the result of Gaullist resistance. Yet despite Monnet’s distaste for French nationalism—and, for that matter, exceptionalism—he saw himself as a patriot whose dream of a European federation was entirely consistent with what was best for his native land.

But today there is an exception to that general principle: the euro, which is the common currency of 18 of the member states of the European Union. The eurozone puts them in the vanguard of the greatest experiment in regional cooperation the world has ever known.

But today there is an exception to that general principle: the euro, which is the common currency of 18 of the member states of the European Union. The eurozone puts them in the vanguard of the greatest experiment in regional cooperation the world has ever known.

Once the contents were bottled, the final stage of the process—selling cases around the world—required this young man of country stock to become a globe-trotting cosmopolitan. He learned English as a child because it was “the language of our clientele,” and traveled widely around Europe as well as North America and the Middle East to promote the Monnet brand with its salamander emblem and, for the longest-aged, top-of-the-line product, the X.O. (“Extra Old”) rating.

Once the contents were bottled, the final stage of the process—selling cases around the world—required this young man of country stock to become a globe-trotting cosmopolitan. He learned English as a child because it was “the language of our clientele,” and traveled widely around Europe as well as North America and the Middle East to promote the Monnet brand with its salamander emblem and, for the longest-aged, top-of-the-line product, the X.O. (“Extra Old”) rating.

Strobe Talbott is president of the Brookings Institution. Talbott, whose career spans journalism, government service, and academe, is an expert on U.S. foreign policy, with specialties on Europe, Russia, South Asia and nuclear arms control. As deputy secretary of state in the Clinton administration, Talbott was deeply involved in both the conduct of U.S. policy abroad and the management of executive branch relations with Congress. He is the author of numerous books including, most recently,

Strobe Talbott is president of the Brookings Institution. Talbott, whose career spans journalism, government service, and academe, is an expert on U.S. foreign policy, with specialties on Europe, Russia, South Asia and nuclear arms control. As deputy secretary of state in the Clinton administration, Talbott was deeply involved in both the conduct of U.S. policy abroad and the management of executive branch relations with Congress. He is the author of numerous books including, most recently,