August 20, 2014

On a warm spring evening in Washington, D.C., a fleet of limousines and town cars delivered hundreds of guests, bedecked in black tie and long gowns, to a gala celebration of the American Dream: the annual awards night for the Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans.

On a warm spring evening in Washington, D.C., a fleet of limousines and town cars delivered hundreds of guests, bedecked in black tie and long gowns, to a gala celebration of the American Dream: the annual awards night for the Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans.

From Farm Boy to Senator: Being the History of the Boyhood and Manhood of Daniel Webster, 1882

source: horatioalgerjr.com

Twelve new members (11 men, one woman) were honored for having risen from childhood poverty to positions as captains of commerce or celebrated public servants. Colin Powell, a 1991 award recipient, was among those in the audience. The new members’ speeches were brief, striking a balance between pride and humility, and all hewing to the rags-to-riches theme: “Who would have thought that I, from a farm in Minnesota/small town in Kansas/Little Rock, raised in an orphanage/with no indoor plumbing/working multiple jobs at 16, would end up running a $6 billion firm/a U.S. ambassador/employing 10,000 people. Only in America!”

The climax of the evening came with the arrival on stage of more than 100 students from poor and troubled backgrounds to whom the Society had awarded college scholarships, an annual rite that over the years has distributed more than $100 million to deserving young people. Tom Selleck read to the 2014 scholars an inspirational passage of poetry from Carol Sapin Gold (“The person who risks nothing does nothing, has nothing and is nothing…”) and the Tenors sang “Forever Young” as a giant American flag was slowly unfurled from the ceiling. The ceremony had the feel of an act of worship and thanksgiving before the altar of the society's namesake. It was a genuinely moving experience, even for me—and I’m a Brit.

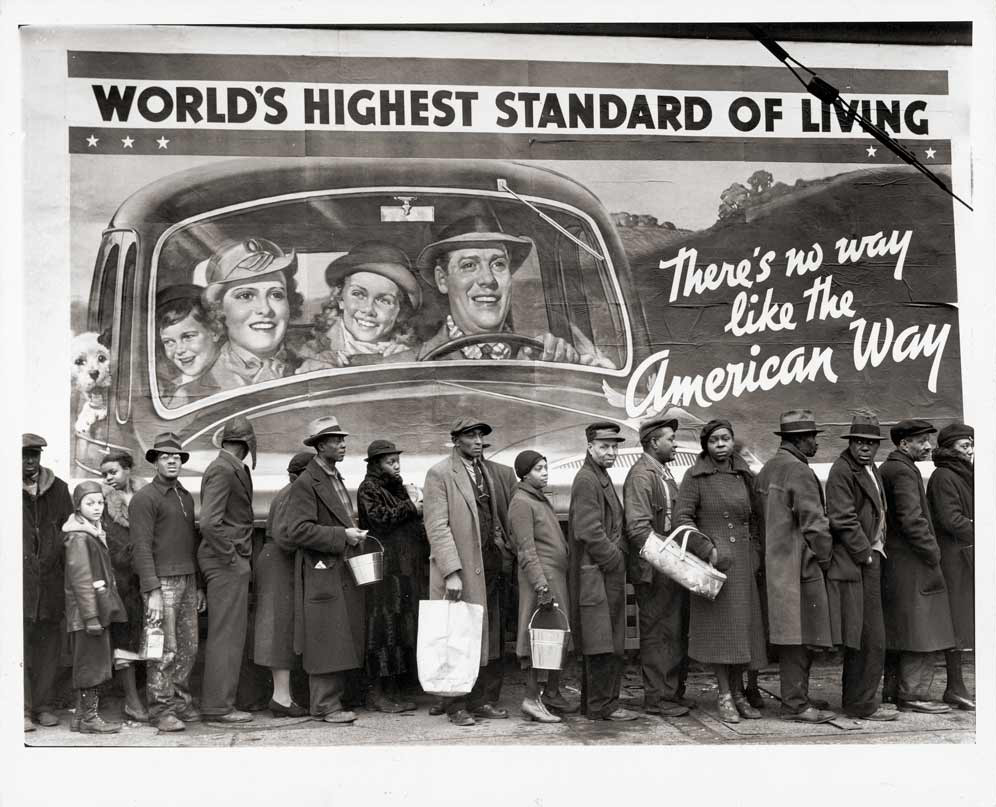

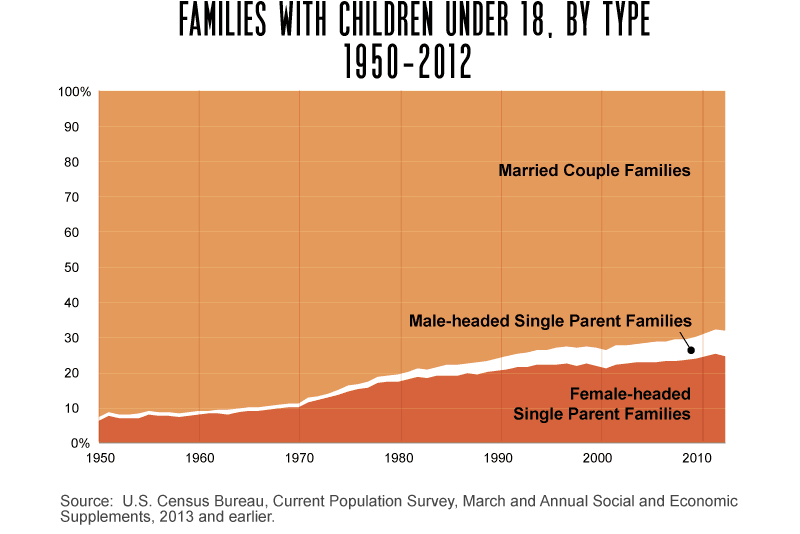

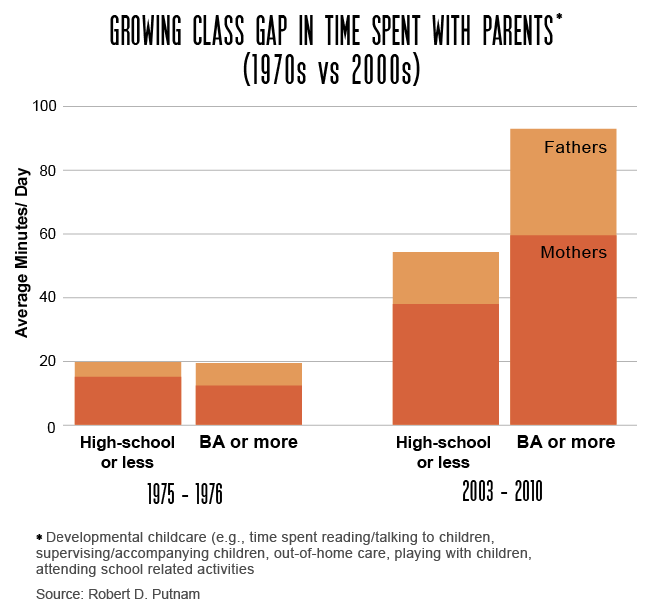

Vivid stories of those who overcome the obstacles of poverty to achieve success are all the more impressive because they are so much the exceptions to the rule. Contrary to the Horatio Alger myth, social mobility rates in the United States are lower than in most of Europe. There are forces at work in America now—forces related not just to income and wealth but also to family structure and education—that put the country at risk of creating an ossified, self-perpetuating class structure, with disastrous implications for opportunity and, by extension, for the very idea of America.

Many countries support the idea of meritocracy, but only in America is equality of opportunity a virtual national religion, reconciling individual liberty—the freedom to get ahead and “make something of yourself”—with societal equality. It is a philosophy of egalitarian individualism. The measure of American equality is not the income gap between the poor and the rich, but the chance to trade places.

In his second inaugural address in 2013, Barack Obama declared: “We are true to our creed when a little girl born into the bleakest poverty knows that she has the same chance to succeed as anybody else, because she is an American; she is free, and she is equal, not just in the eyes of God but also in our own.”

Strive and Succeed, or, The Progress of Walter Conrad, 1908 source: Washburn.edu

President Obama was not saying that every little girl does have that chance, but that she should. The moral claim that each individual has the right to succeed is implicit in our “creed,” the Declaration of Independence, when it proclaims “All men are created equal.” In his first draft of that historic document, Thomas Jefferson was more expansive, writing that all were created “equal and independent.” Although the word was edited out, the sentiment was not.

The Declaration was a statement about the relationship between the United States and Great Britain, but it was also a statement about Americans themselves. The United States was to be a self-made nation comprised of self-made men. Alexis de Tocqueville—the first of many clever Frenchmen to wow the American reading classes—suffused his Democracy in America with admiration of the young nation’s “manly and legitimate passion for equality,” while Abraham Lincoln extolled his countrymen’s “genius for independence.”

There is a simple formula here—equality plus independence adds up to the promise of upward mobility—which creates an appealing image: the nation’s social, political, and economic landscape as a vast, level playing field upon which all individuals can exercise their freedom to succeed. Hence the toddlers who show up at daycare centers in T-shirts emblazoned “Future President.” Hence Americans’ culture of competitiveness, their obsession with sports, their frequent and all-purpose references to “the rules of the game” and to “fairness.” Hence the patriotism-tinged pride of the successful, exulting not only in their own grit and prowess, but also in the meritocratic system that gave them scope and opportunity.

Is America Dreaming?

Richard Reeves explains inequality and opportunity in America, asking “What are your chances of making it from the bottom to the top?”

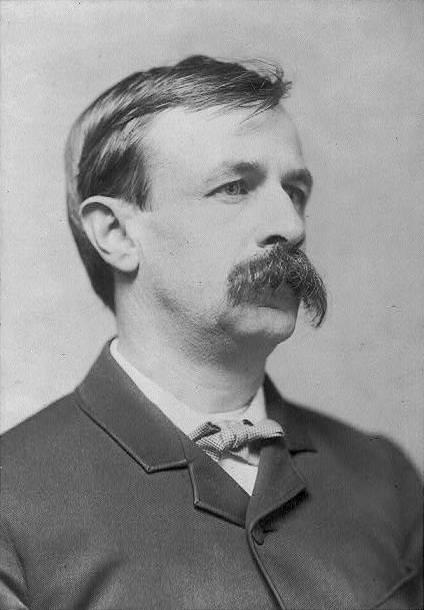

Alger-style upward mobility has always contained at least an element of myth, of course, and the mythmaker himself, Horatio Alger, would almost certainly not have won an award from the society named after him. Alger was born in 1832 into the modest, comfortable home of his Unitarian minister father in Chelsea, Massachusetts, and died in the modest, comfortable home of his sister, 20 miles away in South Natick. Although he enjoyed considerable success with some of his children's books, for the most part he made a barely adequate living from writing, and had to supplement his income with tutoring. Alger’s own life, then, neither started in rags nor ended in riches.

Alger-style upward mobility has always contained at least an element of myth, of course, and the mythmaker himself, Horatio Alger, would almost certainly not have won an award from the society named after him. Alger was born in 1832 into the modest, comfortable home of his Unitarian minister father in Chelsea, Massachusetts, and died in the modest, comfortable home of his sister, 20 miles away in South Natick. Although he enjoyed considerable success with some of his children's books, for the most part he made a barely adequate living from writing, and had to supplement his income with tutoring. Alger’s own life, then, neither started in rags nor ended in riches.

Though Horatio Alger’s own life did not follow the rags-to-riches script, it was almost certainly during his lifetime that his storylines came closest to mirroring real life for many. In the 19th century, the United States pulled immigrants in, pushed its borders out, and allowed men with sharp elbows and big ambitions to make fortunes, vast and fast.

Though Horatio Alger’s own life did not follow the rags-to-riches script, it was almost certainly during his lifetime that his storylines came closest to mirroring real life for many. In the 19th century, the United States pulled immigrants in, pushed its borders out, and allowed men with sharp elbows and big ambitions to make fortunes, vast and fast.

Lack of upward mobility is souring the national mood. As horizons shrink, anger rises. The political right has done a better job, so far, of converting frustration into political gain, by successfully—if implausibly—laying the blame for many of America’s woes at the door of "Big Government". Much of the political energy on the left has been directed against the highest earners—the top 1 percent of the income distribution. But while Occupy Wall Street generated plenty of headlines, it has produced precious few votes, and only a trivial change in the tax system: since 2013, married couples making more than $450,000 a year have had to pay just an extra nickel of tax on each dollar above that level.

Lack of upward mobility is souring the national mood. As horizons shrink, anger rises. The political right has done a better job, so far, of converting frustration into political gain, by successfully—if implausibly—laying the blame for many of America’s woes at the door of "Big Government". Much of the political energy on the left has been directed against the highest earners—the top 1 percent of the income distribution. But while Occupy Wall Street generated plenty of headlines, it has produced precious few votes, and only a trivial change in the tax system: since 2013, married couples making more than $450,000 a year have had to pay just an extra nickel of tax on each dollar above that level.

From the banners of the short-lived Occupy movement to the data tables of countless economic studies, the message is clear: America’s rich are not just getting richer, they are getting much richer. This holds true for both income and—more troubling for opportunity—wealth.

From the banners of the short-lived Occupy movement to the data tables of countless economic studies, the message is clear: America’s rich are not just getting richer, they are getting much richer. This holds true for both income and—more troubling for opportunity—wealth.

Richard V. Reeves is a fellow at Brookings, where his research interests include issues related to social mobility, families and parenting, and inequality. Prior to his Brookings appointment, he was director of strategy to the UK’s Deputy Prime Minister; director of Demos, the London-based political think-tank; and social affairs editor of The Observer newspaper. Richard is also editor-in-chief of Social Mobility Memos, a Brookings blog.

Richard V. Reeves is a fellow at Brookings, where his research interests include issues related to social mobility, families and parenting, and inequality. Prior to his Brookings appointment, he was director of strategy to the UK’s Deputy Prime Minister; director of Demos, the London-based political think-tank; and social affairs editor of The Observer newspaper. Richard is also editor-in-chief of Social Mobility Memos, a Brookings blog.