Minnesota and the surrounding states of the upper Midwest are experiencing a demographic revolution. Yet that fact and its significance are just beginning to sink in, which is why many residents of the greater Minneapolis-St. Paul area, whatever their own ethnicity, still refer to their community matter-of-factly as “lily white.” And while it’s true that with a 78 percent Caucasian population the Twin Cities are still far less ethnically diverse than other parts of the United States — among them the far West and Southeast as well as gateway cities and multicultural hubs like New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, San Francisco, and Miami — it’s also becoming less true with every passing year. One big reason: immigration.

“Our diversity is more diverse.”

Insofar as we associate Minnesota with immigration at all, it’s because of the influx of Scandinavians and Germans during the 19th century (think of all those Norwegian bachelor farmers in Lake Wobegon). But Minnesotans now come from a surprisingly wide array of countries and communities, and these more recent immigrants tend to be people of color rather than whites. As former Minneapolis mayor R.T. Rybak says, “Our diversity is more diverse” than many other places because the state in general, and Minneapolis-St. Paul in particular, have been hubs of refugee resettlement for decades. The region has twice the share of immigrants from Southeast Asia as the United States as a whole (21 percent versus 10 percent of the immigrant population), and five times the share of immigrants from Africa as the nation as a whole (21 percent versus 4 percent).

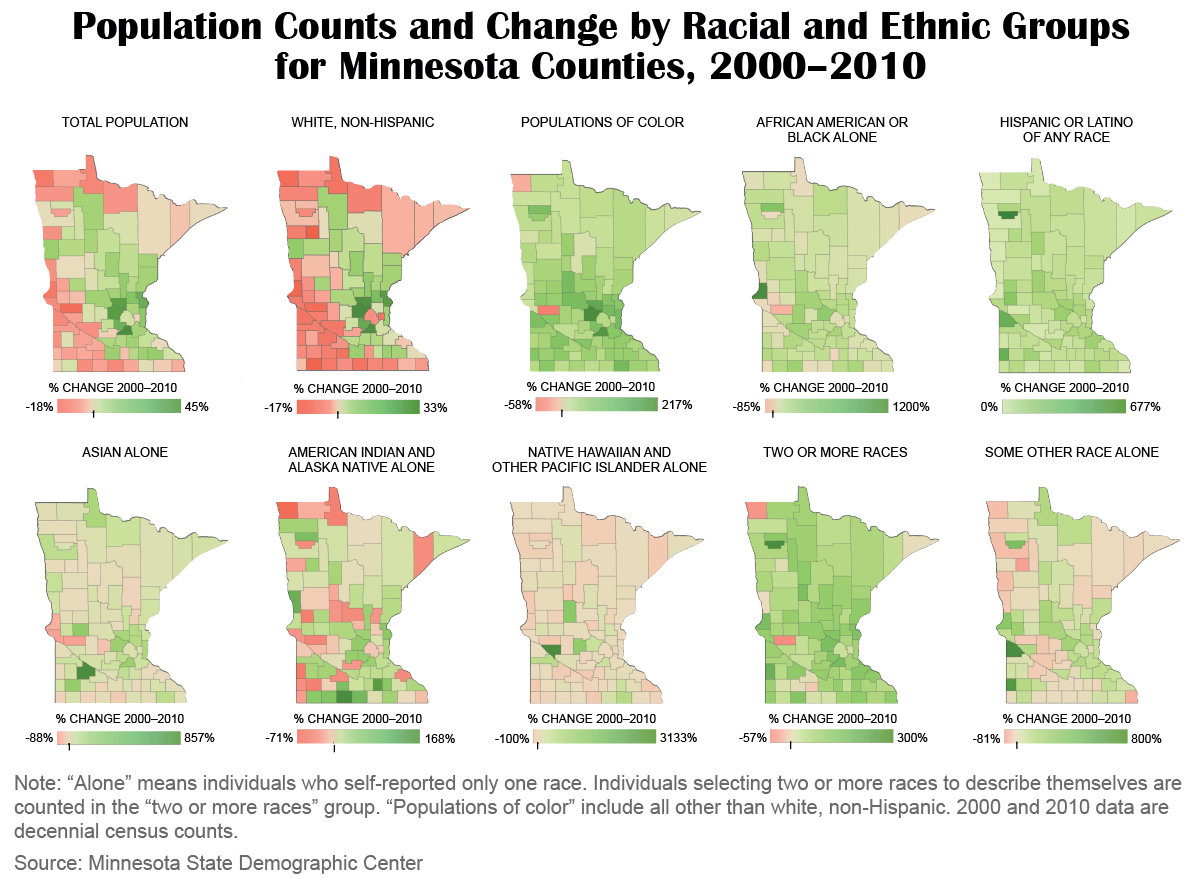

Minnesota is home to Mexicans, Hmong, Indians, Vietnamese, Somalis, Liberians, and Ethiopians. Its people of color also include American-born Native Americans, Hispanics, Asians, and African-Americans. According to the State Demographic Center, the Asian, black, and Hispanic populations in the state tripled between 1990 and 2010, while the white population grew by less than 10 percent. This trend will continue: From 2010 to 2030, the number of people of color is expected to grow twice as quickly as the number of whites. As Minnesota and the region go, so goes the nation, which is also becoming ever more diversified, with an overall decline in the percentage of whites, and increase in people of color.

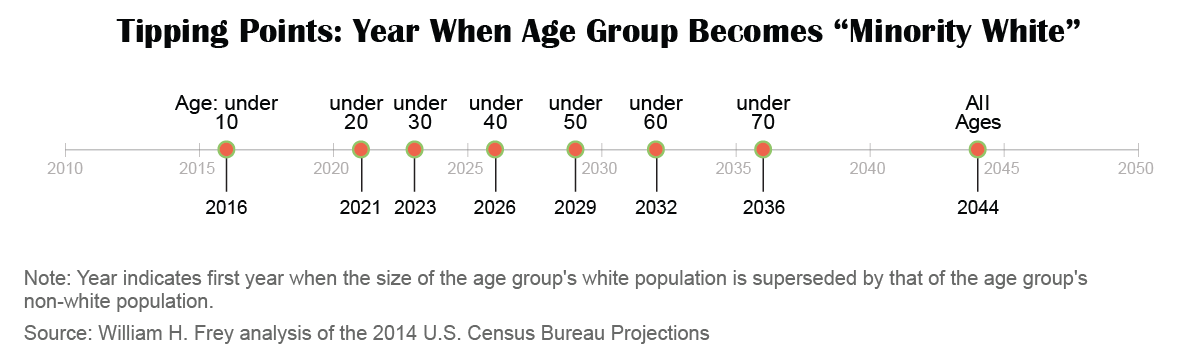

At the same time that its overall ethnic and racial makeup is changing, Minneapolis and St. Paul are feeling the effects of another shift, vividly described by William Frey in his new book, Diversity Explosion, and again one that is occurring throughout the nation: the aging of the generation of Americans born after World War II, who were predominantly white.

These two demographic shifts have huge implications for how both the private and public sectors in Minnesota — and elsewhere — allocate their resources and make decisions about education, training, and hiring. The challenge will be to make sure that as the baby boomers retire and their jobs open up to a more diverse workforce, the young people in that workforce are ready to fill those jobs.

After you’ve read Jennifer Bradley’s microcosm of a changing America in Minnesota, learn more about how these forces are playing out in Frey’s exploration of the country as a whole.

Just as Minneapolis-St. Paul is experiencing profound demographic changes, the entire nation, too, is undergoing what Brookings senior fellow and internationally regarded demographer William H. Frey calls “a diversity explosion.” As Frey documents in his book by that title, America is on the cusp of becoming a country with no racial majority, where new minorities are poised to exert a profound impact on U.S. society, economics, and politics.

With most of the future growth in the labor force coming from people of color, it’s alarming to have to acknowledge how profoundly the existing education and training systems have failed them. Statewide, 85 percent of whites graduated from high school on time in 2013, compared to 58 percent of Hispanics, 57 percent of blacks (including both U.S.-born African-Americans and African immigrants), and fewer than half (49 percent) of American Indians. The gaps are slightly larger at the metropolitan level, and wrenching for the largest city, Minneapolis, where just 51 percent of Africans, 41 percent of Hispanics, 40 percent of African-Americans, and 34 percent of American Indians graduate from public schools on time.

The employment gap is appalling, too. Seventy-nine percent of working-age whites in the Twin Cities are employed compared to 65 percent of working-age people of color — the largest such gap in the country. Unless it can shake these dubious distinctions, the region and the state as a whole will not have a sufficiently skilled workforce to maintain, much less grow, its economy. That could have potentially disastrous results. The region is home to 18 Fortune 500 companies, including 3M, Medtronic, General Mills, and Pillsbury.* If the local workforce cannot meet the needs of these and other companies in the next five to ten years, which is when the state demographic office foresees labor shortages beginning to take effect, they may decide to move to regions that have a bigger pool of qualified workers.

This looming crisis should come as no surprise. Reports dating back as far as the 1990s and early 2000s have repeatedly warned that the education and employment gaps would become a drag on workforce growth and, as a result, on economic growth unless something was done to reverse these trends. Yet little was done, and the gaps persisted.

The lag between awareness and action is partly attributable to complacency. The state has long taken pride in its progressive politics, its iconic-brand companies, and what has, for decades, been the state’s distinctive advantage — a highly skilled workforce. Minnesotans were further lulled by the effects of the Great Recession of 2007-09, when the problem was a scarcity of jobs, not of workers. With a recovery underway, however, Minnesotans have begun to understand that the existing labor pool will soon be insufficient. And this recognition has helped reframe the conversation about race-based education and achievement gaps in Minneapolis-St. Paul — turning what had been a moral (and insufficiently effective) commitment to its underserved communities into an economic necessity. Leading figures from the worlds of government, business, and academia, and public and private groups throughout the region, are now trying to figure out how to undo the effects of decades of neglect, tackling the problem from many perspectives and with an ever greater sense of urgency.

David Hough, the county administrator of Hennepin County, the most populous county in the Twin Cities region, confronts the changing composition of the workforce and the education gap every day. Hough is a baby boomer, as are many other Hennepin County workers. A few years ago, his human resources department ran some numbers to determine how many employees — at what levels and in what departments — were nearing retirement. The results were sobering: somewhere between 2,500 and 3,000 employees “are going to walk out the door” in the next five years, he says, and “we need to make sure we have the next workforce up and ready to go.”

“We’ve always adapted to the education and employment gaps without necessarily taking the problem head on.”

Hough acknowledges that the impending workforce shortage never seemed urgent before. “We’ve always adapted [to the education and employment gaps] without necessarily taking the problem head on.” While he realizes that he doesn’t have to replace the thousands of retirement-eligible baby boomers — more than a third of his workforce — all at once, he knows that the time to begin preparing the next generation of workers is now. “We start with 20 people and 30 people and 40 people,” he says, “hoping that we’re proactive enough so that by 2020 we’ve got some feeder mechanisms [to get people into the jobs pipeline].”

So in 2013 Hough and his colleagues developed a new approach to hiring, finding, and training entry-level workers in about 20 job categories that don’t necessarily require a bachelor’s degree. The county is offering customized training programs for these potential employees at local community colleges and non-profit training organizations, and giving them extensive preparation and support — not just before hiring them but during an internship phase and after they’re on the job. In the pilot program, which started in March 2014, people were trained to be the human services representatives who determine eligibility for social services in Hennepin County. The job is challenging, but the pay is about $18 an hour plus benefits and it can put people on a career ladder in county government. Hough believes the return on investment will be substantial because once these new workers have jobs that pay well, they will no longer need the county public assistance services many of them currently receive. In effect, the program is moving people from one side of the desk to another.

Tamika Hannah is one of the people who has taken advantage of these new opportunities. Even though it has been almost 20 years, she remembers all too well what it was like to be on the recipient side of the desk. Having given birth to two children while still in high school, she moved out on her own at age 18 and had to rely on public assistance to fill the gap in her finances while she was raising a family, going to community college and also holding down a job. “I’ve been the person in the lobby needing assistance, and I know how it feels from that point of view, the looks [the county workers] would give people, like ‘Why did you end up in this situation, why are you down here?’” Years later, now married, with her two older children out of the house and her two younger children (twins) in middle school, Hannah started volunteering at a group called Project for Pride in Living, which, among other things, provides job training for low income people in the Twin Cities. When Hennepin County turned to PPL to run the training program for its human services representatives, starting in the spring of 2014, Hannah jumped at the chance to enroll. She had been looking to get back into the workforce, but her husband’s income couldn’t cover the cost of additional college or training, so the fact that the county training program was free eliminated that obstacle. There was something else driving her, too. “I knew I could deliver a [better] service. I would not look down on these people. I could bring some [personal] humility to this process that is so humiliating to some people.” After training for nine months, she started working for Hennepin County in December. She’s ambitious about her future there. “I’ve picked out my office already,” she says with a laugh. “My supervisor is retiring, and I’ve told her I can [take] her office. I look forward to a long career because there are a lot of people that are retiring. I’m hoping to move my way up and snag some of those positions.”

Susan Haigh is another public official who has tried to make a difference, as the former chair of the Metropolitan Council, the region’s land use, housing, and transportation planning authority. Part of the council’s mission is to maximize opportunities for economic growth in the region. In 2010 the council received a $5 million planning grant from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development. One of the requirements of the grant was that the council prepare a report on the geography of poverty and the geography of opportunity in the region. The report found, not surprisingly, that there was little connection between the two. But what did surprise Haigh and her colleagues was that “racially concentrated areas of poverty” were actually growing in the central cities, and also expanding into the suburbs.

The timing of that research was fortuitous, for it coincided with the Met Council’s once-every-10-year update of its regional plan for water, transportation, and parks, and the first update of its housing strategies in 30 years. Given the evidence of the spread of poverty, and the worsening of ethnic and class separation in the region since 1990, Haigh felt compelled to investigate how public policy might have exacerbated these trends and how new strategies could help it become part of the solution, rather than the problem. As she put it, “How could we not focus on this when we see the starkness of the numbers and the disparities we have? That calls us to action in ways that we haven’t thought of before.”

The council used a portion of the HUD grant and other funding to create a program called Corridors of Opportunity, which would identify changes in the public transit system that could connect people of all incomes and backgrounds to new opportunities for jobs, housing, and other services. In order to engage the people of underserved communities — many of whom were immigrants and people of color — in discussions about transportation needs in their areas, the council distributed $750,000 to organizations in those areas. Many of these organizations had tiny budgets, no understanding of how the Met Council made decisions that literally shaped their communities, and no capacity to analyze technical planning documents or present their own ideas and aspirations to policymakers. So the council asked organizations like Nexus Community Partners to help them figure out how best to use the grants they were given.

Nexus is an organization that supports community-building in impoverished areas and interacts frequently with a wide range of ethnic organizations throughout the region. The head of Nexus, Repa Mekha, feels that over the last four or five years Minneapolis-St. Paul has been able to make a connection between two goals that in other places are not necessarily seen as compatible, much less crucial or on parity with each other: regional economic competitiveness and equity. “If our region is to achieve economic competitiveness, then equity is going to be essential.” Equity, to Mekha, represents more than equality of opportunity. It means “I am a player in this; I am part of the solution, the strategy and the thinking."

“If our region is to achieve economic competitiveness, then equity is going to be essential.”

“Some of the grants we gave organizations were bigger than their existing budgets,” says Mekha, who feels that the money they helped distribute made a real difference in some communities. “They now understand the relationships between their individual work, the work of other [immigrant communities and communities of color] and have the sense that it’s possible to change. … They got to be in the same spaces as decision-makers [and so] … policymakers had to behave in a different kind of way. They couldn’t talk about ‘those people,&rrsquo; when ‘those people’ were in the room. It really did create new environments and space.”

New American Academy, a community organization that serves East African immigrants, primarily in the Twin Cities’ southwest suburbs, received two grants from the council totaling $60,000, and has emerged as one of the Corridors of Opportunity success stories. The organization was founded in 2008 by Asad Aliweyd, a Somali refugee who came to Minnesota in 1997 to seek work in a factory, went on to earn bachelor’s and master’s degrees in St. Paul, and taught high school math for several years in the far-flung suburb of Eden Prairie. After receiving a grant in 2012, New American Academy joined forces with Twin Cities Local Initiatives Support Corp (LISC), another community organization, to focus on identifying transit-oriented development needs in Eden Prairie. When the local Somali and East African community asked that space be made available in the vicinity of the light rail stop in the town center both for small businesses and for affordable housing big enough to accommodate their large, multi-generational households, the two groups began working with the City of Eden Prairie to come up with guidelines to facilitate that kind of development. The city council has accepted their recommendations, but there are still some hurdles to clear with the city administration.

In another venture, in 2013, New American Academy joined forces with Neighborhood Development Centers, which trains and supports entrepreneurs in low-income neighborhoods, to start an 11-week training program to teach Somali and other immigrants the fundamentals of starting a business, from marketing to customer service to establishing a competitive advantage to making financial projections to navigating regulatory systems. So far, five classes of 10–15 people have gone through the program. Although they’ve had difficulty finding affordable spaces for their new businesses adjacent to transit stops, they have been able to start businesses, including a laundry and a home health care agency, nearby. The partners are also working on turning an empty county-owned property in Eden Prairie into a marketplace where Somali and other immigrants can sell food and imported goods to their fellow immigrants and neighbors.

“We really appreciate Nexus and the Met Council’s help,” says Asad Aliweyd. “Before Corridors of Opportunity, we never had a table where we could discuss our needs. Corridors of Opportunities gave us power and a voice to raise our issues, to talk to governments, and to create partnerships with other agencies.”

Click to expand

Minnesota and Minneapolis-St. Paul have high numbers of African and Southeast Asian immigrants largely because of their exceptionally active refugee resettlement voluntary agencies, including Lutheran Social Services, Catholic Charities, and World Relief Minnesota. These agencies participate in an intricate process of resettlement by which refugees are assigned to cities and towns by the federal Office of Refugee Resettlement. The office also provides funds to agencies to enable them to help refugees establish themselves in their new communities. In the late 1970s, Minnesota welcomed Southeast Asian refugees, many of them Hmong people from Laos and Vietnam displaced by the Vietnam War. As the Hmong community in the Twin Cities took root, Hmong living in other cities in the U.S. moved to join what has become one of the largest Hmong communities in the country, comprising about 66,000 people. In the 2000s, refugees from sub-Saharan Africa were resettled in the state and the region. There are about 76,000 African-born blacks in Minnesota, with the majority coming from Somalia, Ethiopia, and Liberia.

The value of this kind of collaborative effort is echoed by Sondra Samuels, an African-American woman who heads up the Northside Achievement Zone (NAZ). Although Samuels grew up in a middle-class family in New Jersey, a number of young African-American men in her family and among her childhood friends were murdered, and the painful memory of those deaths is part of what inspires the work she does today. In a May 2013 interview, she asked: “Why black boys? Why does it happen so often? Why are we okay with it? Why are we acting like it’s normal? What can be done about it? Is this a black problem? Or is this an American problem? How do we solve it? Does anybody care? Our questions actually lay a path for us. … That’s ultimately what led me to here” — here being the Northside, where she works and where she and her family live.

The Northside is one of the poorest neighborhoods in Minneapolis, home to a large black population from the Plains States and the South and, more recently, to a new generation of immigrants from Asia and Latin America. The majority of Northsiders, 59 percent, live below the poverty line, and the neighborhood faces all the challenges that go along with poverty including inadequate transportation connections to job centers, homelessness, violence, and failing schools.

Samuels had spent several years running an anti-violence organization on the Northside, but in 2008, when she concluded that change was not happening fast enough, she and other similarly stymied leaders of community groups joined together and decided to take a more holistic and collaborative approach that addressed the full range of challenges Northsiders faced, while focusing on education, because they view education as a critical factor in breaking the multigenerational cycle of poverty. With support from several philanthropies, they launched NAZ, an ambitious multi-million dollar effort to prepare the 2,500 children living in a 13 by 18 square block area on Minneapolis’s Northside for college. NAZ works with a large number of philanthropies as well as schools, non-profit organizations, and universities to make sure families and children have the necessary supports for learning, which include not just early childhood education, after-school programs, summer classes, and mentoring for children, but more stable housing, parenting education, and career and financial counseling for adults. NAZ’s annual report is explicit about its goal of “turning the social service model on its head. Families are shifting from recipients of services to leaders of a culture shift toward a college-going Northside community.” NAZ has been recognized as a national leader in these kinds of wrap-around services for families, winning a $28 million Promise Neighborhood grant from the U.S. Department of Education in 2011.

Implementing this ambitious model takes time, but NAZ assiduously tracks its impact, and its programs are starting to show results: For example, at the beginning of the 2013-14 school year 49 percent of the NAZ “scholars” who had been enrolled in pre-kindergarten NAZ programs were deemed ready for kindergarten versus 35 percent of the children in North Minneapolis as a whole. NAZ scholars also perform better on third grade reading assessments than their peers, with 22 percent reading at proficiency level compared to 18 percent in the neighborhood as whole, though clearly with figures like those both groups still face huge challenges. But the longer children stay in NAZ programs, the better they seem to do. Third, fourth, and fifth graders who have been enrolled in NAZ efforts for 18 months scored 50 percent higher on state tests than students enrolled with NAZ for less than 6 months. NAZ has not demonstrated the same levels of success for eighth graders, but it has done much less work with that age group, focusing most of its efforts to date on early childhood learning. It now has plans to ramp up its program offerings for older children, starting with extra academic coaching and summer programs.

“It was like an angel coming and sweeping me up and putting me in a place I needed to be.”

NAZ programs can benefit families in a number of ways. Forty-six percent of the unemployed parents who reached out to NAZ for help in their job search actually found work, and a third of the families enrolled in NAZ programs who were at risk of homelessness or serial moves found more stable housing. This last group includes Angela Avent, who enrolled in NAZ in November 2013; within two months she was put in touch with a NAZ partner organization that enrolled her in a subsidy program that reduced what she has to pay in rent to 10 percent of what she was paying before. After years of chaotic housing situations for herself and her four children, she says, “It was like an angel coming and sweeping me up and putting me in a place I needed to be.”

Avent has also benefited from NAZ parenting classes. She was skeptical about the classes at first, but now feels they have helped her become a better mother. She cites several examples of behavioral changes she learned in the classes. Because researchers have found that low-income children hear millions fewer words than children from middle and higher-income homes, and that this gap hurts them academically, the NAZ classes Avent took encouraged her to talk to her children much more, “adding a lot of vocabulary to open their brains,” as she puts it. NAZ classes also taught her to listen to her children — “The more you allow kids to talk, it helps them with emotional growth” — and to find more effective ways of disciplining them. “I can tell my children, ‘Momma doesn’t like it when you do this,’ and give them a [sense of] cause and effect with their actions.” Avent’s children all work with NAZ navigators at their schools and are thriving. Her eldest daughter, who had run away from home, has returned and is making As and Bs, and now tells Avent how proud she is of all her mother has accomplished. The 5-year-old, who had suffered from lead poisoning from a contaminated house they lived in earlier, is getting the speech therapy that he needs and “is a math whiz,” while the youngest will soon start full-time daycare through another NAZ partner organization so that Avent can go to school and pursue her dream of creating her own non-profit organization to support Northside families.

“Too often philanthropic efforts are under-funded and focused on the short-term, because there’s no understanding of how long it can take to achieve meaningful change and how much money is required.”

Some of the philanthropies that support NAZ are also among the 19 private, public, and corporate funders who operate under the umbrella of The Northside Funders Group, as are Hennepin County, LISC, and Nexus. Created in 2008 to change the way philanthropy works on the Northside, the Funders Group is headed by Tawanna Black, a native of Kansas, who came on as executive director in 2013. Black believes that well-targeted infusions of money can indeed alleviate some of the neighborhood’s problems, but she is clear-headed about the fact that it won’t be easy and that if money is not well spent it can sometimes exacerbate problems rather than solving them. “We start with the belief that philanthropy owns some of the problem in North Minneapolis,” Black says, explaining that too often philanthropic efforts are under-funded and focused on the short-term, because there’s no understanding of how long it can take to achieve meaningful change and how much money is required. “Foundation executives often worry that non-profit organizations will get too dependent on a single funder, so they limit their grants to a single year,” but “that doesn’t produce good results,” says Black. “The hard part,” she says, “is how deep a shift in thinking that requires. We’re not talking about a pilot program or a two-year effort. … We’re talking about a 5–10 year commitment, and [dollar] numbers much bigger than what you might have had in mind. … [Because] this problem is bigger and more systemic than most of us could imagine, solutions are more costly and require greater change than we might have thought.”

Sondra Samuels feels that the fact that Northside Funders is coordinating efforts among various philanthropies has been a boon to her work at NAZ. Since Northside’s philanthropies and other funders now operate through committees made up of organizations that fund the same or similar projects, Samuels can have one meeting with the committee comprising her funders, rather than six or seven meetings with the individual foundations, which is a real time and energy saver for her and her staff. Northside has also helped NAZ in the courting of a major new donor, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, by setting up an informational meeting between the Johnson people and the presidents and program officers of some of the foundations that have provided funding for NAZ’s various projects, among them the General Mills Foundation and the McKnight Foundation. “They met and talked about our work in a really knowing and supportive way,” Samuels said, with the result that the Johnson Foundation awarded a $325,000 grant to NAZ. Organizations within Northside Funders have helped Samuels and her partners pay for new slots for NAZ scholars in summer and after-school learning programs, and, most importantly, some of its members, including the McKnight Foundation and the Mortenson Family Foundation, have started giving NAZ multi-year grants, rather than single-year grants.

It’s a matter of pure business necessity. “This is not just about charity or being nice to people of color.”

Like many other community leaders, Black and Samuels consider the economic fate of Minneapolis as a whole to be closely tied to the educational opportunities offered to its poorest citizens. Samuels points out that close to half of the youngest children in the region’s two largest counties are children of color, children who, if trends continue, will not as a group perform as well as their white peers. That’s why the business community is now more engaged than ever before in tackling the challenges of equity; it’s a matter of pure business necessity. “This is not just about charity or being nice to people of color,” as Black says. “Our economic survival as a state depends on figuring out how to close the education and employment gaps. More people are willing to have that conversation than they might have been 5 or 10 years ago, and to do the work [to close the gaps].”

R.T. Rybak, who sits on NAZ’s board and was mayor of Minneapolis from 2002 until 2013, speaks the same language. “We are going to have a worker shortage. … Unless we dramatically improve outcomes for communities of color ….” He, too, views it as not just the right thing to do, but the necessary thing to do. After 9/11 when he saw how unsafe and vilified his many Muslim constituents felt, he looked for ways to better connect their children to the wider community and to jobs. One answer was a summer internship program he founded in 2004 that has since placed thousands of low-income youth — most of them people of color, half of them immigrants — in paying jobs with major regional employers. When he started that program he told prospective employers, “I don’t want you to hire them because you feel sorry for them, but because you need them.”

“America’s antidote to Chinese dominance in Africa is called Minnesota [because] we have hundreds of people born in Africa with family connections who know languages and dialects and are better able to compete.”

He also came to the conclusion that, over the long run, immigrant kids and kids of color are not just an important part of the emerging workforce: they represent a potentially crucial competitive advantage to Minneapolis-St. Paul. If they can get into jobs and work their way up the ladder, they could eventually position their companies to reach more diverse markets. Rybak gives the example of the medical device industry, which is one of the region’s great strengths. “[It’s] a huge industry that is global, and now we have a workforce that speaks more than 100 languages.” He also notes that “We have an emerging industry in water systems, [and demand comes from] places from which we have huge immigration, especially Africa … America’s antidote to Chinese dominance in Africa is called Minnesota [because] we have hundreds of people born in Africa with family connections who know languages and dialects and are better able to compete.”

An article in the Harvard Business Review describes cultural code-switching as one of the “three skills every 21st century manager needs.”

Rybak initially promoted the language skills of immigrant children or those with immigrant parents as an asset to employers, but then realized that African-American children also had cultural skills that employers might need. While they might not be fluent in another language, they are adept at code-switching. Originally code-switching referred to the transition between languages or vernaculars during conversation, but it has taken on a larger meaning, encompassing “the ability, highly prized at … low-income urban schools, to recognize and accurately perform the behaviors appropriate to each different cultural setting,” in the words of education writer Paul Tough. Rybak puts it this way: “If you take a kid from North Minneapolis who goes to high school in Southwest Minneapolis, and then downtown for an internship, that kid code-shifts several times during the day. That’s exactly the skill that 3M will need that person to have if 3M sends him or her to China, Africa, or Eastern Europe. Employers absolutely got that.” An article in Harvard Business Review describes cultural code-switching as one of the “three skills every 21st century manager needs.”

Still, Rybak understands that it all comes back to education. To take on leadership positions and help companies compete globally and engage with many different cultures, children first need to succeed in primary and secondary school, which is why, after his last term as mayor, Rybak signed on as executive director of Generation Next. This is a coalition of leaders from universities, city and county governments, city school systems, major companies, local philanthropies, and non-profit organizations who came together in 2012 to try to eradicate the achievement gap among students in Minneapolis and St. Paul. He sees the education gap as the hardest thing to overcome in the region, and also the most important. Fortunately, the interest in doing something about it crosses party lines. Republicans who control the state House of Representatives have called for education reform to help deal with the gap, and the head of the state Republican Party calls it “arguably the defining issue of our time in Minnesota.”

Closing the education gap in the region is critically important, but by itself may not eradicate the employment disparities between people of color and whites. In Minneapolis–St. Paul and throughout Minnesota, at every level of education except the very highest advanced degrees, people of color as a whole still have notably lower levels of employment, according to the state demographer’s data and other studies. In the Twin Cities, for example, blacks with a GED or high school diploma are three times more likely to be unemployed than whites with the same credentials. In the state as a whole, blacks with bachelors and associates degrees have unemployment rates about twice as a high as whites with those degrees.

Now that Minneapolis-St. Paul’s companies are finding that their customer base is increasingly made up of people of color, who expect to find other people of color on the other side of their business transactions, it’s becoming clear that in order to compete effectively, they will need a team of racially and ethnically diverse employees to connect not just to their customers, but to suppliers and other related businesses. So there are efforts afoot to change the hiring practices and the internal culture of the region’s major employers. This represents a significant shift — the understanding that whites, who make most of the hiring decisions, have to change their behavior and attitudes in order to get more people of color into the workforce and into good jobs, if only because the failure to do so will be reflected in the bottom line.

At least at the professional level, Minneapolis-St. Paul companies have done fairly well over the years at attracting people of color, but they are less successful at keeping them. Business surveys indicate that people of color feel that the region is not sufficiently diverse, and that they have a hard time integrating socially. Company leaders now understand that this is not just a personal problem for their employees, but something with the potential to hurt their businesses, so they are trying to do things differently. For example, while they had previously tried to keep their employees of color from connecting with their peers in other companies, fearing that they might be lured to other jobs, they are now hosting multi-company networking events and connecting their respective African-American, Hispanic, and Asian employee organizations.

“That whole ‘I’m colorblind’ thing has really messed us up, made us believe that [blindness to difference] is a good thing.”

But Tawanna Black of the Northside Funders worries that companies might not fully understand what diversity in the workforce really means. She has been frustrated by the chasm she sees between what corporations say they want and what they actually do in the workplace. She has found that companies say to people of color, “‘You’re so wonderful, we need to have difference,’ then you get hired and they say ‘That’s not how we problem-solve, that’s not how we communicate.’” She wonders whether companies really want diverse perspectives, or just a certain number of people of color on their employment rosters. Black also takes issue with the idea of color-blindness. “I think part of it is, [white] Minnesotans would like to believe that [people of color are] not different, that we just happen to have different skin color. That whole ‘I’m colorblind’ thing has really messed us up, made us believe that [blindness to difference] is a good thing. My ethnicity brings something I don’t need you to dismiss or ignore.” According to research, for companies that value diversity, that “something” can include higher net profit margins, higher return on assets, and higher return on equity than peer firms that are not notably diverse — as long as the diversity is an intrinsic part of the firm’s values, not just superficial window dressing.

Race is certainly now at the center of the political conversation in the state. Minnesota has set aggressive hiring goals for state-funded construction projects, and close to one-third of the people working on the largest construction project in the state, the new professional football stadium in Minneapolis, are people of color. In 2013, the state passed “ban the box” legislation that prevents private employers from asking about criminal history on an initial job application (although employers can ask later in the hiring process and are still allowed to perform criminal background checks). Ban the Box advocates argue that the change opens up more job opportunities for people of color, especially blacks and Hispanics, who are disproportionately convicted of crimes. Target, which is based in Minneapolis-St. Paul, dropped the question from its job applications nationwide after the Minnesota law went into effect.

So, can the state and the Twin Cities go from worst to best in terms of the gaps between whites and people of color? Most people interviewed for this essay believe that the cultural and practical changes necessary to make this leap are taking root. While they say that the region still has a long way to go, they do believe that things will be better for people of color in the future, that the gaps will start to narrow. Sondra Samuels of NAZ speaks of “my hopefulness … Seven hundred parents are working their achievement plans, they are leading this transformation and … transforming the social bedrock.” Moreover, she says, “The business community is really starting to recognize the power and potential of North Minneapolis.” David Hough of Hennepin County is effusive about the hiring efforts the county is making, calling the new approach “the right thing to do … it’s not reactive, it’s proactive, and it’s fun … because we’re helping people.”

Primary working-age population in the United States will experience a net loss of 15 million whites between 2010 and 2030.

Tawanna Black, who in mid-2014 wondered about the region’s commitment to making the changes necessary to bridge the gaps between whites and people of color, sounded more optimistic several months later. “I see people wanting to stay with the conversation, I see people asking the tougher questions and not running from the tough answers. The champions who are stepping up are not just the traditional or expected folks.” While she doesn’t minimize the difficulty of overcoming a legacy of neglect and insensitivity, she thinks that Minnesota is “a perfect example of a state that says, ‘Uh oh, what we did in the past didn’t work, and now we need to do the tough work to keep our economy going.’”

In terms of sheer numbers, Minnesota may still lag in diversity compared to much of the rest of the county, yet it is a microcosm of the kind of changes taking place all across the nation. As William Frey’s Diversity Explosion comprehensively documents, as the baby boom generation ages out of the workforce, the primary working-age population in the United States will experience a net loss of 15 million whites between 2010 and 2030. Meanwhile, the share of people of color that are of labor-force age will steadily grow, especially the youngest segments of the working population. And as immigrants spread out beyond traditional immigrant gateways, and native-born people of color also move to new areas in search of new jobs or a different way of life, more and more communities will face a future that is markedly more ethnically and racially diverse than their past. Between 1990 and 2010, the share of the U.S. population made up of people of color went from 24 percent to 36 percent, and that share is expected to leap to 44.5 percent by 2030. The good news is: The growth of working-age populations of color will enable the United States labor force to grow, albeit modestly, in the 2020s, in contrast to the shrinking workforce populations of much of the developed world, including Japan and many European nations.

Of course that’s only good news if, as Minnesota’s business, civic, and community leaders have recognized, that workforce has been educated and trained to take on the challenges of the 21st century. Minnesota, despite being at the back of the pack because of the huge educational and employment gaps its people of color have faced in the past, seems determined to do the hard work of change, to become a leader in making a virtue of diversity.

So the question that the new demographic reality presents for the country is: Will the U.S. follow in Minnesota’s footsteps? Will market demand do what moral suasion has not, and make the educational, economic, and workplace success of people of color a priority for everyone? Minnesota, and the nation as a whole, will spend the next decade finding out the answer.

Jennifer Bradley is the founding director of the Center for Urban Innovation at the Aspen Institute. She joined Aspen in 2015 after spending seven years as a fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program. While at Brookings, she co-authored with Bruce Katz, The Metropolitan Revolution (Brookings Press, 2013), which explains the critical role of metropolitan areas in the country’s economy, society, and politics. Jennifer has worked extensively on the challenges and opportunities of older industrial cities and has co-authored major economic turnaround strategies for Ohio and Michigan.

Join the conversation on Twitter using #BrookingsEssay or share this on Facebook.

This Essay is also available as an eBook from these online retailers: Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble, Apple iTunes, Google Play, Ebooks.com, and on Kobo.

* The essay originally included Honeywell as among Fortune 500 companies located in the region. Honeywell is headquartered in New Jersey.

Like other products of the Institution, The Brookings Essay is intended to contribute to discussion and stimulate debate on important issues. The views are solely those of the author.