Ibrahim Awwad Ibrahim al-Badri was born in 1971 in Samarra, an ancient Iraqi city on the eastern edge of the Sunni Triangle north of Baghdad. The son of a pious man who taught Quranic recitation in a local mosque, Ibrahim himself was withdrawn, taciturn, and, when he spoke, barely audible. Neighbors who knew him as a teenager remember him as shy and retiring. Even when people crashed into him during friendly soccer matches, his favorite sport, he remained stoic. But photos of him from those years capture another quality: a glowering intensity in the dark eyes beneath his thick, furrowed brow.

Early on, Ibrahim’s nickname was “The Believer.” When he wasn’t in school, he spent much of his time at the local mosque, immersed in his religious studies; and when he came home at the end of the day, according to one of his brothers, Shamsi, he was quick to admonish anyone who strayed from the strictures of Islamic law.

Now Ibrahim al-Badri is known to the world as Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the ruler of the Islamic State or ISIS, and he has the power not just to admonish but to punish and even execute anyone within his territories whose faith is not absolute. His followers call him “Commander of the Believers,” a title reserved for caliphs, the supreme spiritual and temporal rulers of the vast Muslim empire of the Middle Ages. Though his own realm is much smaller, he rules millions of subjects. Some are fanatically loyal to him; many others cower in fear of the bloody consequences for defying his brutal version of Islam.

Since Baghdadi’s sudden emergence from obscurity in 2014 as the monster who ordered and broadcast on YouTube the beheading and even burning alive of those he deemed his enemies, news articles and books have traced his radicalization back to the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003. Although the American invasion fed the fire and enabled it to spread, in fact, his radicalization began much earlier, ignited by an unlikely but highly volatile mixture of fundamentalism, Saddam Hussein’s secular totalitarianism, and his own need to control others.

Baghdadi’s lower middle-class family was known for its piety but also for its proud lineage. His Sunni forefathers claimed to descend from the Prophet Muhammad through the Shiite leaders buried in Samarra’s golden-domed shrine. Baghdadi’s lineage is one instance of the many overlapping religious identities in Iraq that belie the supposedly eternal divide between Sunnis and Shiites. Al-Qaida would bomb the shrine years later after the American invasion in an effort to make that divide a reality.

The family patriarch, Baghdadi’s father Awwad, was active in the religious life of the community. It was at the mosque where his father taught that the teenaged Baghdadi got his own start as a teacher, leading neighborhood children in chanting the Quran. This was his first experience with oratory and religious instruction. When reciting the scripture, a revered vocation in Islam, Baghdadi’s quiet voice would come to life, pronouncing the letters in firm, reverberating tones. He devoted countless hours to mastering the subtleties of the art.

Despite the religiosity of Baghdadi’s family, some of its members joined the Baath Party, a socialist organization dedicated to the goal of pan-Arab union. Although Baathist leaders tolerated and sometimes even encouraged private devotion as an outlet for religious fervor, they were wary of religious activism as a threat to their rule. Baathism had dominated Iraqi politics and the machinery of state since the late 1960s, so citizens who wanted government jobs had to join the party regardless of their personal convictions.

Two of Baghdadi’s uncles served in Saddam’s security services, and one of his brothers became an officer in the army. Another brother who served in the military died during the grueling eight-year war that Iraq fought against Iran in the 1980s with tacit U.S. support. Baghdadi might well have shared that fate had the war continued a little longer and his near-sightedness not disqualified him from military service.

Baghdadi’s family is representative in many ways of the diversity of influences and ever-shifting allegiances that were required for survival in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. Not only did they have ties to the Baathist party, if only for practical purposes, but there is evidence that several of Baghdadi’s family members, perhaps even his father, were Salafis—adherents of an extreme, puritanical form of Sunni Islam widely practiced in Saudi Arabia and throughout much of the Middle East, including Iraq, where it has deep roots. Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, the founder of the Saudi strain of Salafism, supposedly studied in the Iraqi city of Mosul in the 18th century, and individual Salafi missionaries spread their beliefs throughout Iraq in the 20th.

Most Salafis preach obedience to Muslim rulers, even bad ones, but Saddam viewed the Salafis as a threat because they condemn secularism and want states to impose Islamic law. So when the Salafis in Iraq began to organize themselves into societies to further their missionary work in the late 1970s, Saddam put them in jail for forming illegal organizations. He backed off in the 1980s during the war with Shiite Iran because he needed to retain the support of Iraq’s Sunni minority, which includes the Salafis. But in 1990, two years after the war with Iran ended, Saddam pressured thousands of Salafis to sign a pledge not to convert other Iraqis to their cause.

Hover over shapes for more information (tap on touch device)

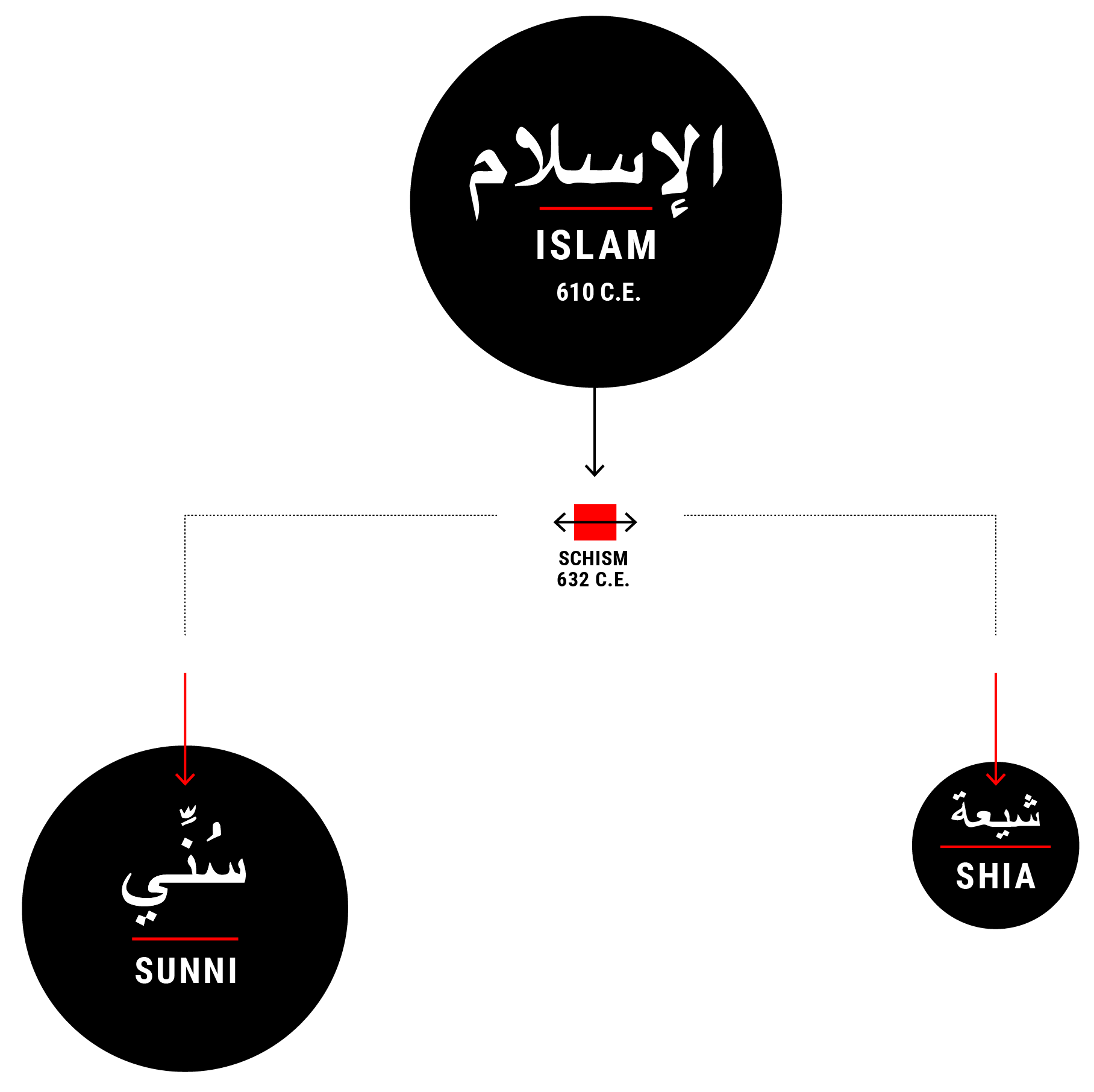

Islam is the world’s second-largest religion, with 1.6 billion followers. It began in the 7th century when the Prophet Muhammad claimed to receive revelations from God, which make up the Quran. • Its five basic duties include the acceptance of monotheism and that Muhammad is the messenger of Allah, daily prayer, charity, fasting during Ramadan, and making a pilgrimage to Mecca.

After Muhammad’s death in 632, a disagreement over his rightful successor cleaved Islam in two. However, Sunni and Shiite Muslims have lived together peacefully for centuries. • In recent years, the rift has been exacerbated by extremist groups like the Islamic State who have attacked Shiite Muslims in Iraq and Syria.

Most Muslims are Sunni— 85–90% worldwide—but they are the minority in Iraq. • They believe that Muhammad's succession is not dependent on direct lineage. Jihadist Salafism, a radical fundamentalist strain espoused by the Islamic State and al-Qaida, is an offshoot of Sunni Islam.

Shiite Muslims comprise 10–15% of Islam worldwide, yet they constitute the majority in Iraq and Iran. • They believe that Muhammad’s successor must be a direct descendant.

Around the same time, Saddam sought to co-opt his devout subjects by founding in 1989—and naming in his own honor—the Saddam University for Islamic Studies. The university was but one of the many ways he attempted to use religion to strengthen his hold on Iraqi society. As part of what he called his Faith Campaign, which began in 1993, he tried to woo religious conservatives by closing nightclubs, forbidding public consumption of alcohol, and imposing some of the harsh penalties prescribed by Islamic scripture such as severing a hand or foot for theft. In 1994, he confided in a cabinet meeting that his earlier hesitancy about applying Islamic punishments was unwarranted. Such punishments, he observed, could deter crime better than less severe ones. Left unsaid was the fact that they were also useful for frightening his subjects into submission while burnishing his credentials as defender of the faith.

As part of his Faith Campaign, Saddam also promoted the study and recitation of the Quran, promising to use state funds to train 30,000 Quran instructors. Saddam even donated 28 liters of his own blood to be used as ink for a Quran to be housed in the Mother of All Battles Mosque.

Saddam’s creation of new jobs teaching the scripture may have influenced Baghdadi’s academic career. Unable to study law at the University of Baghdad as he wanted because of his middling grades in high school—he nearly failed English—Baghdadi studied the Quran there instead.

When Baghdadi graduated from the University of Baghdad in 1996, he enrolled in the recently-established Saddam University for Islamic Studies where he studied for a master’s in Quranic recitation, his favorite subject. His family’s Baathist connections undoubtedly helped him get into the highly-selective graduate program. Baghdadi’s master’s thesis was a commentary on an obscure medieval text on Quranic recitation. His task was to reconcile various versions of the manuscript. While tedious, it involved little imagination and no questioning of the content—a perfect project for a dogmatist. He received his master’s degree in 1999 and immediately enrolled in Saddam University’s doctoral program in Quranic studies.

During Baghdadi’s time in graduate school, his paternal uncle, Ismail al-Badri, persuaded him to join the Muslim Brotherhood, a transnational movement dedicated to establishing states governed by Islamic law. In most countries the Brotherhood, which has both liberal and conservative members, had adopted a cautious approach to political change, confined to working within the system. Many of the Brothers in Baghdad, including the ones Baghdadi fell in with at first, were peaceful Salafis who wanted states to impose Islamic law but didn’t advocate revolt if the states fail to do so. But Baghdadi quickly gravitated toward those few Salafis whose strict creed led them to call for the overthrow of rulers they considered betrayers of the faith. They called themselves jihadist Salafis. Baghdadi’s older brother, Jum`a, was part of this movement. So was Baghdadi’s mentor, Muhammad Hardan, a one-time member of the Brotherhood who had fought in the war against the Soviets in Afghanistan in the 1980s.

Baghdadi threw himself into the writings of those Muslim Brothers who had embraced jihadism. Under their tutelage he grew increasingly impatient with the Brotherhood mainstream, which he felt was made up of “people of words, not action.”

By 2000, Baghdadi was already spoiling for a fight.

Most of what we know about Baghdadi between 2000 and 2004 pertains to his personal life, and even that is extremely sketchy. He seems to have had two wives and six children. His first wife, Asma, was the daughter of his maternal uncle. He married his second wife, Isra, later, probably after the U.S. invasion in 2003. Like other conservative Muslims, Baghdadi kept his wives from public view, and he didn’t mix much socially himself, preferring to spend time with his family in their small apartment near the Haji Zaydan mosque in the poor Tobchi neighborhood of Baghdad. There he taught Quranic recitation to the neighborhood children and chanted the call to prayer over the mosque’s loudspeakers in his sonorous voice.

The mosque was also the place that allowed him to indulge his other passion—for the game of soccer. The mosque had a soccer club, and Baghdadi was the star, remembered as “our Messi,” a reference to the great Argentinian soccer star Lionel Messi. Teammates recall that he often lost his temper when he failed to score.

His temper could also be ignited by the sight of what he considered un-Islamic behavior. According to a neighbor of Baghdadi’s at the time, who was quoted in an article published in The Telegraph last year, he became extremely upset one day when he witnessed members of a wedding party engaging in an activity that appalled him. “How can men and women be dancing together like this?” he exclaimed. Baghdadi forced the revelers to stop.

Late in 2003, after the Americans had defeated and disbanded Saddam’s army, Baghdadi helped found Jaysh Ahl al-Sunna wa-l-Jamaah (Army of the People of the Sunna and Communal Solidarity), an insurgent group that fought U.S. troops and their local allies in northern and central Iraq.

Soon after, in February 2004, Baghdadi was arrested in Fallujah while visiting a friend who was on the American wanted list. He was transferred to a detention facility at Camp Bucca, a sprawling complex in southern Iraq. Prison files classified him as a “civilian detainee,” which meant his captors didn’t know he was a jihadist.

For the ten months he remained in custody, Baghdadi hid his militancy and devoted himself to religious instruction. “Baghdadi was a quiet person,” remembers an anonymous fellow inmate interviewed by The Guardian. “He has a charisma. You could feel that he was someone important.” Baghdadi led prayers, preached Friday sermons, and conducted religious classes for other prisoners.

Once again he dazzled his comrades—and, no doubt, his jailers—on the soccer field. And yet again he was compared to an Argentinian great: his nickname at Camp Bucca was “Maradona.”

Baghdadi ingratiated himself with both the Sunni inmates and the Americans, looking for opportunities to negotiate with the camp authorities and mediate between rival groups of prisoners.

“Every time there was a problem in the camp,” recalls The Guardian’s source, “he was at the center of it. He wanted to be the head of the prison—and when I look back now, he was using a policy of conquer and divide to get what he wanted, which was status. And it worked.”

Many of the 24,000 inmates at Bucca were Sunni Arabs who had served in Saddam’s military and intelligence services. When Saddam fell, so did they, a consequence of the American purge of the Baathists and the new ascendency of Iraq’s long-oppressed Shiite majority. If they weren’t jihadists when they arrived, many of them were by the time they left. Radical jihadist manifestos circulated freely under the eyes of the watchful but clueless Americans.

“If there was no American prison in Iraq, there would be no Islamic State now.”

- former camp bucca inmate

“New recruits were prepared so that when they were freed they were ticking time bombs,” remembers another fellow inmate, who was interviewed by a reporter with Al Monitor. When a new prisoner came in, his peers would “teach him, indoctrinate him, and give him direction so he leaves a burning flame.” Baghdadi would turn out to be the most explosive of those flames, a man responsible for much of the conflagration that would engulf the region less than a decade later.

Many of the ex-Baathists at Bucca, some of whom Baghdadi befriended, would later rise with him through the ranks of the Islamic State. “If there was no American prison in Iraq, there would be no [Islamic State] now,” recalled the inmate interviewed by The Guardian. “Bucca was a factory. It made us all. It built our ideology.” The prisoners dubbed the camp “The Academy,” and during his ten months in residence, Baghdadi was one of its faculty members.

By the time Baghdadi was released on December 8, 2004, he had a virtual Rolodex for reconnecting with his co-conspirators and protégés: they had written one another’s phone numbers in the elastic of their underwear.

Just two months before Baghdadi’s release, al-Qaida established a branch of its terror network in Iraq by absorbing a jihadist militia run by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and putting him in charge of it. Zarqawi, a Jordanian who wanted to create an Islamic state, thought he could use al-Qaida in Iraq (AQI) to provoke a sectarian civil war between Iraq’s minority Sunnis and the majority Shiites, which would force the Sunnis to turn to his group for protection. Once AQI emerged victorious from the ensuing bloodbath, as he expected it to do, there would be no serious obstacles to establishing the Islamic state he dreamed of. Al-Qaida’s leaders reluctantly agreed to Zarqawi’s brutal program because they wanted a hand in the new insurgency against the Americans. But they quickly came to regret their endorsement when the shocking violence of Zarqawi’s group, which he publicized online, alienated the Muslim masses whose support al-Qaida cultivated to prosecute its global war on America and its allies.

Baghdadi would almost certainly have met jihadists in Zarqawi’s circle during his time in Bucca, and would doubtless have been attracted to a jihadist group even more extreme than his own. After his release from Bucca, Baghdadi called a relative in al-Qaida, who connected him with a spokesman for the group in Iraq. The spokesman convinced Baghdadi to go to Damascus to perform tasks for al-Qaida, assuring him that he could also finish his dissertation while he was working for them. Academically-trained religious scholars are rare in jihadist organizations, so it made sense to send a budding scholar to Syria where the Americans wouldn’t be able to get their hands on him. Once he was there, Baghdadi set about his assigned task of ensuring that AQI’s online propaganda was in line with its brand of ultraconservative Islam. Baghdadi’s tribal connections in Iraq and his ties with other jihadist groups there must have also come in handy, because on several occasions he was able to help foreign jihadists cross Syria’s border into his native land. At the time, Syria’s President, Bashar al-Assad, was turning a blind eye to the foreign fighter pipeline into Iraq in order to punish the United States for invading the country; that same pipeline would one day flow in the opposite direction after Assad’s citizens revolted against him in 2011.

In 2006, al-Qaida in Iraq formed an umbrella organization for jihadist groups resisting the American occupation. Baghdadi’s group was one of the first to join. Soon after, Zarqawi declared his intent to establish an Islamic state, directly countermanding al-Qaida’s instructions to wait until after the Americans had withdrawn and AQI secured popular support for establishing the state. When Zarqawi was killed in a U.S. airstrike in June, his successor, Abu Ayyub al-Masri, an Egyptian jihadist, went ahead with the plan. He proclaimed the founding of the Islamic State in October and dissolved AQI, announcing that its soldiers were now part of the Islamic State. Masri assumed the title of minister of war although he actually ran the new organization; the titular emir of the group, Abu Umar, an Iraqi, was just a figurehead in the beginning.

The new leaders of the Islamic State pledged private oaths of allegiance to Osama bin Laden, but in public they maintained the fiction that the State was independent of al-Qaida. They hoped outsiders would think of their organization as an independent state or even the beginnings of a restored caliphate, the far-flung empire of early Islam. The ambiguity surrounding their relationship would later lead to conflict between the two organizations.

Because of his scholarly credentials, Baghdadi was put in charge of the Islamic State’s religious affairs in some of its Iraqi “provinces.” Because the group did not yet actually control any territory, this largely meant that Baghdadi continued to be responsible for ensuring that the Islamic State’s propaganda reflected its creed, and that its foot soldiers abided by its strictures and implemented the harsh punishments prescribed by Islamic scripture wherever and whenever they could. Accused adulterers whom they managed to capture were stoned, alcohol drinkers were whipped, thieves had their hands amputated, and “apostates”—anyone who defied the Islamic State’s program—were executed.

Taking a break from his pastoral duties, Baghdadi showed up in Baghdad on March 13, 2007, to defend his dissertation. It was yet another critical edition of a medieval book about Quranic recitation—this time a commentary on a poem about how to recite the Quran. Baghdadi’s advisor in Tikrit couldn’t attend because of the violence raging across Iraq, so he sent in comments on the dissertation, pointing out some errors and suggesting some revisions. But overall he was happy with his student’s work, and Baghdadi received his Ph.D. in Quranic Sciences with a grade of “very good” for his dissertation.

ISIS STONES THE ACCUSED ADULTERERS IT CAPTURES, WHIPS ALCOHOL DRINKERS, AMPUTATES THE HANDS OF THIEVES, AND EXECUTES APOSTATES.

Baghdadi’s newly-minted scholarly credentials as well as the work he had done managing the Islamic State’s religious affairs brought him to the attention of Masri, who appointed him supervisor of the Sharia Committee, hence the enforcer of all the Islamic State’s religious strictures. Masri also named him to the 11-member Consultative Council. The council ostensibly advised the emir, Abu Umar, but was actually controlled by Masri, whose support came from his fellow foreign jihadists. When Baghdadi joined the council, the Iraqi members were growing restless and had rallied around their countryman Abu Umar, hoping for a greater say in the decision-making.

Much as he had done in Camp Bucca, Baghdadi quickly found a role as a conciliator between the two sides. Despite being a Masri protégé, Baghdadi earned enough of Abu Umar’s trust to be appointed to the Islamic State’s Coordination Committee, a powerful three-man panel that could select, supervise, and fire the Islamic State’s commanders in the group’s Iraqi provinces. Baghdadi drafted messages on Abu Umar’s behalf to his al-Qaida boss, Osama bin Laden. He also coordinated communication between the Islamic State’s top leaders and their provincial representatives, much of which was conducted by couriers.

In early 2010, the Iraqis captured one of these couriers, a man who carried messages between Abu Umar and the Islamic State’s commander in Baghdad, Manaf al-Rawi. According to one insider account, a mole in the Iraqi security service warned Baghdadi that al-Rawi was in danger, but Baghdadi failed to pass on the warning. Perhaps Baghdadi worried more about saving his own skin than protecting his bosses—communicating with them after the courier’s capture could have exposed him to danger. Whatever the case, the captured courier led the Iraqi authorities to al-Rawi, who, under interrogation, gave his captors information that enabled a U.S.-Iraqi force in April 2010 to surround the mud house outside Tikrit where Abu Umar and Masri were hiding. The two blew themselves up rather than surrender.

With their deaths, the Islamic State faced its first leadership succession. The Consultative Council couldn’t meet in conclave to choose a new emir since that might have ended with another American-led raid and another multiple suicide. Bin Laden, who still had the allegiance of the Islamic State, issued instructions to the Consultative Council to appoint an interim leader and to send him a list of candidates for emir and their qualifications.

With the death of the Islamic State’s commanders, the head of the Islamic State’s military council, Hajji Bakr, was suddenly in a position to manipulate the succession. A former officer in Saddam’s army who had served time in Camp Bucca after Baghdadi’s release, Bakr was tainted as the former servant of an impious regime and therefore not a contender for supreme leadership himself, so he set about to be the kingmaker and the power behind the throne. Ignoring bin Laden’s instructions, Hajji Bakr polled the 11 members of the Consultative Council on their preferences. But he reportedly rigged the outcome by writing a letter to each saying that all of the others were in favor of Baghdadi. Perhaps the cagey colonel believed the young Baghdadi would be more pliable than the other contenders, or that he would be less loyal to the Islamic State’s distant lords in al-Qaida, who constantly objected to the Islamic State’s brutal brand of insurgency. In making the case for Baghdadi, Hajji Bakr would undoubtedly have extolled Baghdadi’s lineage from the Prophet, his mastery of the Quran, and his managerial experience in the organization.

The council elected the new emir of the Islamic State by a vote of 9 to 2. It was then that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, at the age of 39, took his now-famous nom de guerre, a double homage to his faith and his native land. Abu Bakr was Muhammad’s father-in-law and, after the Prophet’s death, the first caliph; Baghdad was the capital of the grandest caliphate in early Islam, the Abbasid dynasty. The Abbasids had swept to power in the eighth century using clever apocalyptic propaganda and clandestine networks to mobilize popular anger against the ruling regime in Damascus. Baghdadi was clearly hoping to repeat the performance on the same stage.

With the new emir’s blessing, not to mention gratitude, Hajji Bakr set about purging the ranks of the Islamic State of anyone who could challenge Baghdadi’s authority. Dubbed by Islamic State insiders as the “prince of shadows” and the emir’s “private minister,” Hajji Bakr settled scores and eliminated rivals through intimidation and assassination, much as Saddam had done.

The power had now shifted from the foreign fighters to the Iraqi members of the Islamic State. As American and Iraqi forces killed or captured the previous emir’s commanders, their replacements were often, like Baghdadi and Hajji Bakr, former prisoners from Camp Bucca. And many, like Bakr, were also former officers in Saddam’s military or intelligence services. Such men would prove useful in running a new authoritarian state.

Secure on the throne, Baghdadi and his éminence grise set about reviving the Islamic State’s flagging fortunes. Military setbacks had forced the group underground in 2008 and subsequent attacks like the one on Abu Umar and Masri had decimated its command structure. Baghdadi and Hajji Bakr were determined to bring the fight out in the open again and seize the territory necessary for establishing a caliphate. The growing unrest in Syria in 2011 played directly into their hands. Presented with an opportunity to inject violence into what had been a peaceful revolt, Baghdadi sent one of his Syrian operatives to set up a secret branch of the Islamic State in the country that year. The branch, later known as the Nusra Front, initially followed the Islamic State’s playbook by attacking civilians as part of a clandestine terror campaign to sow chaos. The hope was that the Islamic State would be able to capitalize on that chaos in order to make its first land grab.

Syrian President Assad lumped these attacks on civilians with the actions of those who had been protesting his regime to claim that the peaceful protestors were really nothing but terrorists. But as Nusra evolved into an insurgent organization, it became more careful about killing Sunni civilians and more dedicated to working with other Sunni rebel factions to oust Assad. This shift also reflected the guidance Nusra received from al-Qaida’s new emir, Ayman al-Zawahiri, who had replaced bin Laden after he was killed by U.S. Navy SEALs in May 2011. Zawahiri believed it was wiser to cultivate popular support before trying to establish an Islamic state, so he called on Nusra to collaborate with the other rebels.

Baghdadi disagreed with Zawahiri, to whom he had pledged a private oath of allegiance. As he saw things, there was already an Islamic State; it just needed to be made real by territorial conquest in Syria. Nusra’s cooperation with the other Sunni rebels was thwarting that plan.

BAGHDADI IMPOSES HARSH RELIGIOUS LAWS AS A WAY OF LEGITIMIZING HIS STATE, TERRIFYING LOCAL POPULATIONS INTO SUBMISSION.

In the spring of 2013, Baghdadi ordered his subordinates in Nusra to comply with his strategy; they refused. Furious, Baghdadi announced publicly that Nusra was part of the Islamic State, which he renamed the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. Nusra’s leader responded by repudiating Baghdadi’s authority and pledging his own direct oath of allegiance to Zawahiri. When Zawahiri accepted the oath of Nusra’s leader and ordered Baghdadi to concern himself only with Iraq, he refused. Baghdadi wanted control of Syria as well. Under Baghdadi’s leadership the Islamic State began to gobble up territory in eastern Syria, pushing out other Sunni rebel groups including Nusra. Zawahiri had no choice but to expel the Islamic State from al-Qaida, which he did in February 2014. In the ensuing melee between Nusra and the Islamic State, the latter came out on top: The State consolidated its hold on eastern Syria and siphoned off the bulk of Nusra’s foreign fighter contingent, whose members were more interested in setting up a state of their own than trying to topple Assad’s.

Soon after, reports began to circulate about how the Islamic State governed its new lands. Baghdadi had previously been able to inflict Islamic punishments only on those who were unlucky enough to be captured by the Islamic State insurgent group, because the group was not yet in control of any territory. But now Baghdadi was the head of a government that reigned over much of eastern Syria, and he could impose his will over hundreds of thousands of people, especially those in the Islamic State’s stronghold of Raqqa. Baghdadi ordered Christians to pay a protection tax or face death. Subjects accused of theft had their hands amputated; those accused of adultery were whipped or stoned to death. Although these punishments are found in Islamic scripture, most Muslim countries have abandoned them as outmoded. Even al-Qaida’s leaders had counseled their affiliates to apply the punishments leniently. But Baghdadi viewed imposing the harsh religious laws as a way of legitimizing his new state as “Islamic,” and terrifying the local population into submission. Like Saddam, he understood the political utility of brutality in the name of religion.

In the same vein, Baghdadi labeled Muslims who resisted his rule as apostates. Recalcitrant Sunni tribesmen and captured government soldiers were executed en masse and dumped into anonymous graves, a warning to anyone who would defy him.

His rule in eastern Syria secure, Baghdadi set his sights on seizing adjoining land in western Iraq.

Since early 2014, the Islamic State had made steady gains in western Iraq. The Sunnis living there were angry at the Shiite-dominated government in Baghdad for shutting them out of the military and ejecting them from the halls of power after the Americans left. When Sunni tribes in western Iraq began fighting against the government in late 2013, Baghdadi ordered his soldiers to join the fray. Religious zealots, tribesmen, and Baathist secularists fought side-by-side in common cause to throw off Shiite rule. In the winter and spring of 2014, the Islamic State made inroads in Fallujah and Ramadi by working with its allies. State fighters rounded up policemen and soldiers who resisted and filmed their gruesome executions. The videos spread rapidly among Iraq’s military and security services.

In June 2014, the Islamic State and its allies launched a lightning attack on Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city. They captured the city with little effort, its garrison force and local police too demoralized and too terrified by the videos to stand and fight.

With that victory, the Islamic State dominated territory in eastern Syria and western Iraq that stretched roughly the distance between Washington, D.C., and Cleveland, Ohio. Later that month, the Islamic State’s spokesman proclaimed the return of God’s kingdom on earth, the caliphate, and Baghdadi reverted to his given name, preceded now with the ultimate title: Caliph Ibrahim. To justify this outsized claim, his supporters circulated the genealogy of his tribe, which traced its lineage back to Muhammad’s descendants. This was considered an important qualification, for some Islamic prophecies of the End Times say a man descended from the Prophet will one day rule as caliph—an office that hasn’t existed since the fall of the Ottoman Empire after World War I.

The so-called caliph ascended to the pulpit in Mosul days later to deliver the Friday sermon, his first and only public appearance since taking the helm of the Islamic State in 2010. He wore black robes to evoke the memory of the Abbasid caliphs who had ruled from Baghdad; they, too, had come to power by claiming descent from the Prophet’s family and promising a return to pristine Islam.

THE BARE FACTS OF BAGHDADI’S BIOGRAPHY SHOW AN UNUSUALLY CAPABLE MAN. HE HELPED FOUND AN INSURGENT GROUP, FINISHED A PH.D. WHILE MANAGING THE RELIGIOUS AFFAIRS OF THE ISLAMIC STATE, BUILT COALITIONS, AND INTIMIDATED RIVALS.

“I was appointed to rule you but I am not the best among you,” he proclaimed. “If you see me acting truly, then follow me. If you see me acting falsely, then advise and guide me…. If I disobey God, then do not obey me.” This was a paraphrase of what the first caliph, Abu Bakr, had said when he was elected by Muhammad’s comrades.

The capture of Mosul convinced the hitherto-reluctant American government that it had to act. American planes began dropping bombs on Islamic State positions soon after. In reprisal, the Islamic State beheaded its Western captives. They went to their deaths dressed in orange jumpsuits like those worn by many Iraqis in U.S. custody during the previous decade, a grim form of televised revenge that had originated with Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the Jordanian founder of al-Qaida in Iraq, after the revelations from Abu Ghraib prison. Another American hostage, aid worker Kayla Mueller, was repeatedly raped by Baghdadi in the home of a henchman. Baghdadi justified the sex slavery, like the beheadings, on religious grounds.

Since Baghdadi’s sermon, the media has twice reported that he was killed or seriously wounded by airstrikes, first in November 2014 and again in March 2015. But in May 2015 the secretive leader of the Islamic State reemerged to issue a statement over the Internet offering both guidance and proof of life to his legion of followers.

Still, the near misses raise the question of what would happen if Baghdadi dies in office. The answer depends on what one makes of his life. For some, Baghdadi is just a cipher, manipulated by non-religious ex-Baathists or thugs who are using the Islamic State to attain power. Or he’s a cog in a machine, an expression of an impersonal institution or historical forces. These views at least agree that Baghdadi is not his own man; his sins are the sins of others, perhaps Saddam Hussein, perhaps George W. Bush, perhaps a cabal of former regime loyalists. If Baghdadi disappears, the argument goes, he will just be replaced by a new mindless figurehead.

But the bare facts of Baghdadi’s biography show an unusually capable man. He helped found an insurgent group, finished a Ph.D. while managing the religious affairs of the Islamic State, and has been able to prevail amid the State’s cutthroat politics because of his skill at coalition building and his ability to intimidate his rivals. The consolidation of the Islamic State’s territorial gains in Syria and its rapid expansion into Iraq came after the death of his “prince of shadows.” Although the New York Times recently reported that he himself is making arrangements for a succession in the event of his demise by devolving many of his military powers to subordinates, his blend of religious scholarship and political cunning won’t be easily replaced. None of his possible successors combine his Prophetic lineage, religious knowledge, and skill at winning powerful friends and quieting dissent.

Throughout his life, Baghdadi has chosen the path of religious extremism, and in ways as small as denouncing dancers at a wedding and as large as mass executions he has always attempted to impose his views on others. He could have been a university professor, persuading young minds with argument. But the believer became the commander of the believers, seeking to impose his savagely bleak religious vision on the entire world. “The march of the mujahidin will continue until they reach Rome,” he proclaimed last year. If Baghdadi’s life is a cautionary tale, it is about the danger of creating the chaos that allows men like him to flourish.

William McCants is a fellow in the Center for Middle East Policy and director of the Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World. He is also an adjunct faculty member at Johns Hopkins University and has served in government and think tank positions related to Islam, the Middle East and terrorism, including as State Department senior adviser for countering violent extremism. He is the author of Founding Gods, Inventing Nations: Conquest and Culture Myths from Antiquity to Islam.

Join the conversation on Twitter using #BrookingsEssay.

Sign up for email and be the first to hear about new Brookings Essays and other related research from Brookings.

This Essay is also available as an eBook from these online retailers: Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble, Google Play, and Ebooks.com.

Like other products of the Institution, The Brookings Essay is intended to contribute to discussion and stimulate debate on important issues. The views are solely those of the author.

Graphics and design by Jessica K Pavone. Web development by Marcia Underwood. Illustrations by Sareen Hairabedian. Video by Brookings Creative Lab. Research by Fred Dews, Thomas Young, and Jessica K Pavone. Editorial by Beth Rashbaum and Fred Dews.